Cirrhosis

| Cirrhosis | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Cirrhosis of the liver, hepatic cirrhosis |

| |

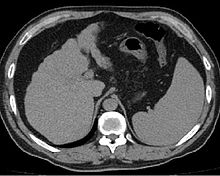

| Cross-section of human liver with cirrhosis | |

| Pronunciation | |

| Specialty | Gastroenterology, Hepatology |

| Symptoms | Fatigue, itchiness, swelling in the lower legs, jaundice, easily bruising, fluid build-up in the abdomen[1] |

| Complications | Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, hepatic encephalopathy, dilated veins in the esophagus, liver cancer[1] |

| Usual onset | Over months, years or decades[1] |

| Duration | Long term[1] |

| Causes | Alcoholic liver disease, hepatitis B, hepatitis C, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) |

| Diagnostic method | Blood tests, medical imaging, liver biopsy[2][1] |

| Prevention | Vaccination (such as for hepatitis B), avoiding alcohol,[1] losing weight, exercising, low-carbohydrate diet, controlling hypertension and diabetes may help in those with NAFLD or NASH |

| Treatment | Depends on underlying cause[3] |

| Frequency | 2.8 million (2015)[4] |

| Deaths | 1.3 million (2015)[5] |

Cirrhosis, also known as liver cirrhosis or hepatic cirrhosis, chronic liver failure or chronic hepatic failure and end-stage liver disease, is an acute condition of the liver in which the normal functioning tissue, or parenchyma, is replaced with scar tissue (fibrosis) and regenerative nodules as a result of chronic liver disease.[6][7][8] Damage to the liver leads to repair of liver tissue and subsequent formation of scar tissue. Over time, scar tissue and nodules of regenerating hepatocytes can replace the parenchyma, causing increased resistance to blood flow in the liver's capillaries—the hepatic sinusoids[9]: 83 —and consequently portal hypertension, as well as impairment in other aspects of liver function.[6][10] The disease typically develops slowly over months or years.[1]

Stages of cirrhosis include compensated cirrhosis and decompensated cirrhosis.[11][12]: 110–111 Early symptoms may include tiredness, weakness, loss of appetite, unexplained weight loss, nausea and vomiting, and discomfort in the right upper quadrant of the abdomen.[13] As the disease worsens, symptoms may include itchiness, swelling in the lower legs, fluid build-up in the abdomen, jaundice, bruising easily, and the development of spider-like blood vessels in the skin.[13] The fluid build-up in the abdomen may develop into spontaneous infections.[1] More serious complications include hepatic encephalopathy, bleeding from dilated veins in the esophagus, stomach, or intestines, and liver cancer.[14]

Cirrhosis is most commonly caused by medical conditions including alcohol-related liver disease, metabolic dysfunction–associated steatohepatitis (MASH – the progressive form of metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease,[15] previously called non-alcoholic fatty liver disease or NAFLD[16]), heroin abuse,[17] chronic hepatitis B, and chronic hepatitis C.[13][18] Chronic heavy drinking can cause alcoholic liver disease.[19] Liver damage has also been attributed to heroin usage over an extended period of time as well.[20] MASH has several causes, including obesity, high blood pressure, abnormal levels of cholesterol, type 2 diabetes, and metabolic syndrome.[21] Less common causes of cirrhosis include autoimmune hepatitis, primary biliary cholangitis, and primary sclerosing cholangitis that disrupts bile duct function, genetic disorders such as Wilson's disease and hereditary hemochromatosis, and chronic heart failure with liver congestion.[13]

Diagnosis is based on blood tests, medical imaging, and liver biopsy.[2][1]

Hepatitis B vaccine can prevent hepatitis B and the development of cirrhosis from it, but no vaccination against hepatitis C is available.[1] No specific treatment for cirrhosis is known, but many of the underlying causes may be treated by medications that may slow or prevent worsening of the condition.[3] Hepatitis B and C may be treatable with antiviral medications.[1] Avoiding alcohol is recommended in all cases.[1] Autoimmune hepatitis may be treated with steroid medications.[1] Ursodiol may be useful if the disease is due to blockage of the bile duct.[1] Other medications may be useful for complications such as abdominal or leg swelling, hepatic encephalopathy, and dilated esophageal veins.[1] If cirrhosis leads to liver failure, a liver transplant may be an option.[21] Biannual screening for liver cancer using abdominal ultrasound, possibly with additional blood tests, is recommended[22][23] due to the high risk of hepatocellular carcinoma arising from dysplastic nodules.[24]

Cirrhosis affected about 2.8 million people and resulted in 1.3 million deaths in 2015.[4][5] Of these deaths, alcohol caused 348,000 (27%), hepatitis C caused 326,000 (25%), and hepatitis B caused 371,000 (28%).[5] In the United States, more men die of cirrhosis than women.[1] The first known description of the condition is by Hippocrates in the fifth century BCE.[25] The term "cirrhosis" was derived in 1819 from the Greek word "kirrhos", which describes the yellowish color of a diseased liver.[26]

Signs and symptoms

[edit]

Cirrhosis can take quite a long time to develop, and symptoms may be slow to emerge.[13] Some early symptoms include tiredness, weakness, loss of appetite, weight loss, and nausea.[13] Early signs may also include redness on the palms known as palmar erythema.[11] People may also feel discomfort in the right upper abdomen around the liver.[13]

As cirrhosis progresses, symptoms may include neurological changes affecting both the peripheral and central nervous systems, disrupting the neurotransmission within the brain and causing neuromuscular fatigue.[13][27] This can consist of cognitive impairments, confusion, memory loss, sleep disorders, and personality changes.[13]Steatorrhea or presence of undigested fats in stool is also a symptom of cirrhosis.[28]

Worsening cirrhosis can cause a build-up of fluid in different parts of the body such as the legs (edema) and abdomen (ascites).[13] Other signs of advancing disease include itchy skin, bruising easily, dark urine, and yellowing of the skin.[13]

Liver dysfunction

[edit]These features are a direct consequence of liver cells not functioning:

- Spider angiomata or spider nevi happen when there is dilatation of vasculature beneath the skin surface.[29] There is a central, red spot with reddish extensions that radiate outward. This creates a visual effect that resembles a spider. It occurs in about one-third of cases.[29] The likely cause is an increase in estrogen.[29] Cirrhosis causes a rise of estrogen due to increased conversion of androgens into estrogen.[30]

- Palmar erythema, a reddening of the palm below the thumb and little finger, is seen in about 23% of cirrhosis cases, and results from increased circulating estrogen levels.[31]

- Gynecomastia, or the increase of breast size in men, is caused by increased estradiol (a potent type of estrogen).[32] This can occur in up to two-thirds of cases.[33]

- Hypogonadism signifies a decreased functionality of the gonads.[34] This can result in impotence, infertility, loss of sexual drive, and testicular atrophy. A swollen scrotum may also be evident.[35]

- Liver size can be enlarged, normal, or shrunken in people with cirrhosis.[36] As the disease progresses, the liver will typically shrink due to the result of scarring.[37]

- Jaundice is the yellowing of the skin. It can additionally cause yellowing of mucous membranes notably of the white of the eyes. This phenomenon is due to increased levels of bilirubin, which may also cause the urine to be dark-colored.[38]

Portal hypertension

[edit]Liver cirrhosis makes it hard for blood to flow in the portal venous system.[39] This resistance creates a backup of blood and increases pressure.[39] This results in portal hypertension. Effects of portal hypertension include:

- Ascites is a build-up of fluid in the peritoneal cavity in the abdomen[40]

- An enlarged spleen in 35–50% of cases[6]

- Esophageal varices and gastric varices result from collateral circulation in the esophagus and stomach (a process called portacaval anastomosis).[41] When the blood vessels in this circulation become enlarged, they are called varices. Varices are more likely to rupture at this point.[9] Variceal rupture often leads to severe bleeding, which can be fatal.[41]

- Caput medusae are dilated paraumbilical collateral veins due to portal hypertension.[39] Blood from the portal venous system may be forced through the paraumbilical veins and ultimately to the abdominal wall veins. The created pattern resembles the head of Medusa, hence the name.[9]

- Cruveilhier-Baumgarten bruit is bruit in the epigastric region (on examination by stethoscope).[42] It is due to extra connections forming between the portal system and the paraumbilical veins.[42]

Other nonspecific signs

[edit]Some signs that may be present include changes in the nails (such as Muehrcke's lines, Terry's nails, and nail clubbing).[43][44] Additional changes may be seen in the hands (Dupuytren's contracture) as well as the skin/bones (hypertrophic osteoarthropathy).[33]

Advanced disease

[edit]As the disease progresses, complications may develop. In some people, these may be the first signs of the disease.

- Bruising and bleeding can result from decreased production of blood clotting factors.[45]

- Hepatic encephalopathy (HE) occurs when ammonia and related substances build up in the blood.[45] This build-up affects brain function when they are not cleared from the blood by the liver. Symptoms can include unresponsiveness, forgetfulness, trouble concentrating, changes in sleep habits, or psychosis. One classic physical examination finding is asterixis.[33] This is the asynchronous flapping of outstretched, dorsiflexed hands.[33] Fetor hepaticus is a musty breath odor resulting from increased dimethyl sulfide and is a feature of HE.[46]

- Increased sensitivity to medication can be caused by decreased metabolism of the active compounds.[47]

- Acute kidney injury (particularly hepatorenal syndrome).[33]

- Cachexia associated with muscle wasting and weakness.[45]

Causes

[edit]Cirrhosis has many possible causes, and more than one cause may be present. History taking is of importance in trying to determine the most likely cause.[2] Globally, 57% of cirrhosis is attributable to either hepatitis B (30%) or hepatitis C (27%).[48][49] Alcohol use disorder is another major cause, accounting for about 20–40% of the cases.[49][33]

Common causes

[edit]

- Alcoholic liver disease (ALD, or alcoholic cirrhosis) develops for 10–20% of individuals who drink heavily for a decade or more.[50] Alcohol seems to injure the liver by blocking the normal metabolism of protein, fats, and carbohydrates.[51] This injury happens through the formation of acetaldehyde from alcohol. Acetaldehyde is reactive and leads to the accumulation of other reactive products in the liver.[33] People with ALD may also have concurrent alcoholic hepatitis. Associated symptoms are fever, hepatomegaly, jaundice, and anorexia.[51] AST and ALT blood levels are both elevated, but at less than 300 IU/liter, with an AST:ALT ratio > 2.0, a value rarely seen in other liver diseases.[52] In the United States, 40% of cirrhosis-related deaths are due to alcohol.[33]

- In non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), fat builds up in the liver and eventually causes scar tissue.[53] This type of disorder can be caused by obesity, diabetes, malnutrition, coronary artery disease, and steroids.[53][54] Though similar in signs to alcoholic liver disease, no history of notable alcohol use is found. Blood tests and medical imaging are used to diagnose NAFLD and NASH, and sometimes a liver biopsy is needed.[40]

- Chronic hepatitis C, an infection with the hepatitis C virus, causes inflammation of the liver and a variable grade of damage to the organ.[45] Over several decades, this inflammation and damage can lead to cirrhosis. Among people with chronic hepatitis C, 20–30% develop cirrhosis.[45][33] Cirrhosis caused by hepatitis C and alcoholic liver disease are the most common reasons for liver transplant.[33] Both hepatitis C and hepatitis B–related cirrhosis can also be attributed with heroin addiction.[55]

- Chronic hepatitis B causes liver inflammation and injury that over several decades can lead to cirrhosis.[45] Hepatitis D is dependent on the presence of hepatitis B and accelerates cirrhosis in co-infection.[45]

Less common causes

[edit]- In primary biliary cholangitis (previously known as primary biliary cirrhosis), the bile ducts become damaged by an autoimmune process.[45] This leads to liver damage.[53] Some people may have no symptoms, while others may present with fatigue, pruritus, or skin hyperpigmentation.[56] The liver is typically enlarged which is referred to as hepatomegaly.[56] Rises in alkaline phosphatase, cholesterol, and bilirubin levels occur. Patients are usually positive for anti-mitochondrial antibodies.[56]

- Primary sclerosing cholangitis is a disorder of the bile ducts that presents with pruritus, steatorrhea, fat-soluble vitamin deficiencies, and metabolic bone disease. A strong association with inflammatory bowel disease is seen, especially ulcerative colitis.[33]

- Autoimmune hepatitis is caused by an attack of the liver by lymphocytes. This causes inflammation and eventually scarring as well as cirrhosis. Findings include elevations in serum globulins, especially gamma globulins.[33]

- Hereditary hemochromatosis usually presents with skin hyperpigmentation, diabetes mellitus, pseudogout, or cardiomyopathy. All of these are due to signs of iron overload.[33][45] Family history of cirrhosis is common as well.

- Wilson's disease is an autosomal recessive disorder characterized by low ceruloplasmin in the blood and increased copper of the liver.[53][45] Copper in the urine is also elevated. People with Wilson's disease may also have Kayser–Fleischer rings in the cornea and altered mental status.[53][45]

- Indian childhood cirrhosis is a form of neonatal cholestasis characterized by deposition of copper in the liver [45][57]

- Alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency is an autosomal co-dominant disorder of low levels of the enzyme alpha-1 antitrypsin[33]

- Cardiac cirrhosis is due to chronic right-sided heart failure, which leads to liver congestion [33]

- Galactosemia[58]

- Glycogen storage disease type IV[45]

- Cystic fibrosis[33]

- Hepatotoxic drugs or toxins, such as acetaminophen (paracetamol), methotrexate, or amiodarone[45]

Pathophysiology

[edit]The liver plays a vital role in many metabolic processes in the body including protein synthesis, detoxification, nutrient storage (such as glycogen), platelet production and clearance of bilirubin. With progressive liver damage; hepatocyte death and replacement of functional liver tissue with fibrosis in cirrhosis, these processes are disrupted. This leads to many of the metabolic derangements and symptoms seen in cirrhosis.[59]

Cirrhosis is often preceded by hepatitis and fatty liver (steatosis), independent of the cause. If the cause is removed at this stage, the changes are fully reversible.[citation needed]

The pathological hallmark of cirrhosis is the development of scar tissue that replaces normal tissue, which is normally organized into lobules. This scar tissue blocks the portal flow of blood through the organ, raising the blood pressure.[59] This manifests as portal hypertension in which the pressure gradient between the portal circulation as compared to the systemic circulation is elevated. This portal hypertension leads to decreased sinusoidal flow from liver cells to nearby sinusoids in the liver, and increased lymph production with extravasation of lymph to the extracellular space, causing ascites.[59] This also causes reduced cardiac return and central blood volume, which activates the renin-angiotensin system (RAAS) which causes kidneys to reabsorb sodium and water, causing water retention and further ascites. Activation of the RAAS also causes kidney vasoconstriction and may cause kidney injury.[59]

Research has shown the pivotal role of the stellate cell, that normally stores vitamin A, in the development of cirrhosis. Damage to the liver tissue from inflammation leads to the activation of stellate cells, which increases fibrosis through the production of myofibroblasts, and obstructs hepatic blood flow.[60] In addition, stellate cells secrete TGF beta 1, which leads to a fibrotic response and proliferation of connective tissue. TGF-β1 have been implicated in the process of activating hepatic stellate cells (HSCs) with the magnitude of fibrosis being in proportion to increase in TGF β levels. ACTA2 is associated with TGF β pathway that enhances contractile properties of HSCs leading to fibrosis.[61] Furthermore, HSCs secrete TIMP1 and TIMP2, naturally occurring inhibitors of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), which prevent MMPs from breaking down the fibrotic material in the extracellular matrix.[62][63]

As this cascade of processes continues, fibrous tissue bands (septa) separate hepatocyte nodules, which eventually replace the entire liver architecture, leading to decreased blood flow throughout. The spleen becomes congested, and enlarged, resulting in its retention of platelets, which are needed for normal blood clotting. Portal hypertension is responsible for the most severe complications of cirrhosis.[citation needed]

Diagnosis

[edit]

The diagnosis of cirrhosis in an individual is based on multiple factors.[33] Cirrhosis may be suspected from laboratory findings, physical exam, and the person's medical history. Imaging is generally obtained to evaluate the liver.[33] A liver biopsy will confirm the diagnosis; however, is generally not required.[45]

Imaging

[edit]Ultrasound is routinely used in the evaluation of cirrhosis.[45] It may show a small and shrunken liver in advanced disease. On ultrasound, there is increased echogenicity with irregular appearing areas.[64] Other suggestive findings are an enlarged caudate lobe, liver surface nodularity[65] widening of the fissures and enlargement of the spleen.[66] An enlarged spleen, which normally measures less than 11–12 cm (4.3–4.7 in) in adults, may suggest underlying portal hypertension.[67] Ultrasound may also screen for hepatocellular carcinoma and portal hypertension.[45] This is done by assessing flow in the hepatic vein.[68] An increased portal vein pulsatility may be seen. However, this may be a sign of elevated right atrial pressure.[69] Portal vein pulsatility are usually measured by a pulsatility indices (PI).[68] A number above a certain values indicates cirrhosis (see table below).

| Index | Calculation | Cutoff |

|---|---|---|

| Average-based | (Max – Min) / Average[68] | 0.5[68] |

| Max-relative | (Max – Min) / Max[70] | 0.5[70][71]–0.54[71] |

Other scans include CT of the abdomen and MRI.[45] A CT scan is non-invasive and may be helpful in the diagnosis.[45] Compared to the ultrasound, CT scans tend to be more expensive. MRI provides excellent evaluation; however, is a high expense.[45]

Portable ultrasound is a low cost tool to identify the sign of liver surface nodularity with a good diagnostic accuracy.[72]

Cirrhosis is also diagnosable through a variety of new elastography techniques.[73][74] When a liver becomes cirrhotic it will generally become stiffer. Determining the stiffness through imaging can determine the location and severity of disease. Techniques include transient elastography, acoustic radiation force impulse imaging, supersonic shear imaging and magnetic resonance elastography.[75] Transient elastography and magnetic resonance elastography can help identify the stage of fibrosis.[76] Compared to a biopsy, elastography can sample a much larger area and is painless.[77] It shows a reasonable correlation with the severity of cirrhosis.[76] Other modalities have been introduced which are incorporated into ultrasonagraphy systems. These include 2-dimensional shear wave elastography and point shear wave elastography which uses acoustic radiation force impulse imaging.[16]

Rarely are diseases of the bile ducts, such as primary sclerosing cholangitis, causes of cirrhosis.[45] Imaging of the bile ducts, such as ERCP or MRCP (MRI of biliary tract and pancreas) may aid in the diagnosis.[45]

Lab findings

[edit]The best predictors of cirrhosis are ascites, platelet count < 160,000/mm3, spider angiomata, and a Bonacini cirrhosis discriminant score greater than 7 (as the sum of scores for platelet count, ALT/AST ratio and INR as per table).[78]

| Score | Platelet count x109 | ALT/AST ratio | INR |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | >340 | >1.7 | <1.1 |

| 1 | 280-340 | 1.2-1.7 | 1.1-1.4 |

| 2 | 220-279 | 0.6-1.19 | >1.4 |

| 3 | 160–219 | <0.6 | ... |

| 4 | 100-159 | ... | ... |

| 5 | 40-99 | ... | ... |

| 6 | <40 | ... | ... |

These findings are typical in cirrhosis:

- Thrombocytopenia, typically multifactorial, is due to alcoholic marrow suppression, sepsis, lack of folate, platelet sequestering in the spleen, and decreased thrombopoietin.[52] However, this rarely results in a platelet count < 50,000/mL.[80]

- Aminotransferases AST and ALT are moderately elevated, with AST > ALT. However, normal aminotransferase levels do not preclude cirrhosis.[52]

- Alkaline phosphatase – slightly elevated but less than 2–3 times the upper limit of normal.[citation needed]

- Gamma-glutamyl transferase – correlates with AP levels. Typically much higher in chronic liver disease from alcohol.[80]

- Bilirubin levels are normal when compensated, but may elevate as cirrhosis progresses.[citation needed]

- Albumin levels fall as the synthetic function of the liver declines with worsening cirrhosis since albumin is exclusively synthesized in the liver.

- Prothrombin time increases, since the liver synthesizes clotting factors.

- Globulins increase due to shunting of bacterial antigens away from the liver to lymphoid tissue.

- Serum sodium levels fall(hyponatremia) due to inability to excrete free water resulting from high levels of ADH and aldosterone.

- Leukopenia and neutropenia are due to splenomegaly with splenic margination.[citation needed]

- Coagulation defects occur, as the liver produces most of the coagulation factors, thus coagulopathy correlates with worsening liver disease.

- Glucagon is increased in cirrhosis.[33]

- Vasoactive intestinal peptide is increased as blood is shunted into the intestinal system because of portal hypertension.

- Vasodilators are increased (such as nitric oxide and carbon monoxide) reducing afterload with compensatory increase in cardiac output, mixed venous oxygen saturation.[81]

- Renin is increased (as well as sodium retention in kidneys) secondary to a fall in systemic vascular resistance.[82]

FibroTest is a biomarker for fibrosis that may be used instead of a biopsy.[83]

Other laboratory studies performed in newly diagnosed cirrhosis may include:

- Serology for hepatitis viruses, autoantibodies (ANA, anti-smooth muscle, antimitochondria, anti-LKM)

- Ferritin[84][85] and transferrin saturation: markers of iron overload as in hemochromatosis, copper and ceruloplasmin: markers of copper overload as in Wilson's disease

- Immunoglobulin levels (IgG, IgM, IgA) – these immunoglobins are nonspecific, but may help in distinguishing various causes.

- IgG level is elevated in chronic hepatitis, alcoholic and autoimmune hepatitis. It's slow and sustained increase is seen in viral hepatitis.

- IgM significantly increased in primary biliary cirrhosis and moderately increased in viral hepatitis and cirrhosis.

- IgA is increased in alcoholic cirrhosis and primary biliary cirrhosis.[citation needed]

- Cholesterol and glucose

- Alpha 1-antitrypsin

Markers of inflammation and immune cell activation are typically elevated in cirrhotic patients, especially in the decompensated disease stage:

- C-reactive protein (CRP)[86]

- Procalcitonin (PCT)[86]

- Presepsin[87]

- soluble CD14[86]

- soluble CD163[88]

- soluble CD206 (mannose receptor)[89]

- soluble TREM-1[90]

The link between gut microbiota constitution and liver health (Particularly in Cirrhosis) has been well described,[91] however specific biomarkers for prediction of Cirrhosis still requires further research. A 2014 study identified 15 microbial biomarkers from the gut microbiota.[92] These could potentially be used to discriminate patients with liver cirrhosis from healthy individuals.

Pathology

[edit]

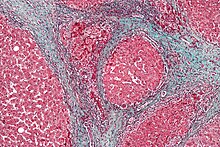

The gold standard for diagnosis of cirrhosis is a liver biopsy. This is usually carried out as a fine-needle approach, through the skin (percutaneous), or internal jugular vein (transjugular).[93] Endoscopic ultrasound-guided liver biopsy (EUS), using the percutaneous or transjugular route, has become a good alternative to use.[94][93] EUS can target liver areas that are widely separated,[95] and can deliver bi-lobar biopsies.[94] A biopsy is not necessary if the clinical, laboratory, and radiologic data suggest cirrhosis. Furthermore, a small but significant risk of complications is associated with liver biopsy, and cirrhosis itself predisposes for complications caused by liver biopsy.[96]

Once the biopsy is obtained, a pathologist will study the sample. Cirrhosis is defined by its features on microscopy: (1) the presence of regenerating nodules of hepatocytes and (2) the presence of fibrosis, or the deposition of connective tissue between these nodules. The pattern of fibrosis seen can depend on the underlying insult that led to cirrhosis. Fibrosis can also proliferate even if the underlying process that caused it has resolved or ceased. The fibrosis in cirrhosis can lead to destruction of other normal tissues in the liver: including the sinusoids, the space of Disse, and other vascular structures, which leads to altered resistance to blood flow in the liver, and portal hypertension.[97]

-

No fibrosis, but mild zone 3 steatosis, in which collagen fibres (pink–red, arrow) are confined to portal tracts (P) (Van Gieson's stain)[98]

-

Histopathology of steatohepatitis with mild fibrosis in the form of fibrous expansion (Van Gieson's stain)[98]

-

Histopathology of steatohepatitis with moderate fibrosis, with thin fibrous bridges (Van Gieson's stain)[98]

-

Histopathology of steatohepatitis with established cirrhosis, with thick bands of fibrosis (Van Gieson's stain)[98]

-

Trichrome stain, showing cirrhosis as a nodular texture surrounded by fibrosis (wherein collagen is stained blue).

As cirrhosis can be caused by many different entities which injure the liver in different ways, cause-specific abnormalities may be seen. For example, in chronic hepatitis B, there is infiltration of the liver parenchyma with lymphocytes.[97] In congestive hepatopathy there are erythrocytes and a greater amount of fibrosis in the tissue surrounding the hepatic veins.[99] In primary biliary cholangitis, there is fibrosis around the bile duct, the presence of granulomas and pooling of bile.[100] Lastly in alcoholic cirrhosis, there is infiltration of the liver with neutrophils.[97]

Macroscopically, the liver is initially enlarged, but with the progression of the disease, it becomes smaller. Its surface is irregular, the consistency is firm, and if associated with steatosis the color is yellow. Depending on the size of the nodules, there are three macroscopic types: micronodular, macronodular, and mixed cirrhosis. In the micronodular form (Laennec's cirrhosis or portal cirrhosis), regenerating nodules are under 3 mm. In macronodular cirrhosis (post-necrotic cirrhosis), the nodules are larger than 3 mm. Mixed cirrhosis consists of nodules of different sizes.[101]

-

Micronodular cirrhosis, with diffuse areas of pallor

-

Pale macronodules of cirrhosis

-

Cirrhosis leading to hepatocellular carcinoma

Grading

[edit]The severity of cirrhosis is commonly classified with the Child–Pugh score (also known as the Child–Pugh–Turcotte score).[102] This system was devised in 1964 by Child and Turcotte, and modified in 1973 by Pugh and others.[103] It was first established to determine who would benefit from elective surgery for portal decompression.[102] This scoring system uses multiple lab values including bilirubin, albumin, and INR.[104] The presence of ascites and severity of encephalopathy is also included in the scoring.[104] The classification system includes class A, B, or C.[104] Class A has a favorable prognosis while class C is at high risk of death.

| Child-Pugh Class | Points | Liver Function | Prognosis | Abdominal surgery post-operative mortality |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child-Pugh Class A | 5–6 points | Good liver function | 15–20 years | 10% |

| Child-Pugh Class B | 7–9 points | Moderately impaired liver function | 30% | |

| Child-Pugh Class C | 10–15 points | Advanced liver dysfunction | 1–3 years | 82% |

The Child-Pugh score is a validated predictor of mortality after a major surgery.[102] For example, Child class A patients have a 10% mortality rate and Child class B patients have a 30% mortality rate while Child class C patients have a 70–80% mortality rate after abdominal surgery.[102] Elective surgery is usually reserved for those in Child class A patients. There is an increased risk for Child class B individuals and they may require medical optimization. Overall, it is not recommended for Child class C patients to undergo elective surgery.[102]

In the past, the Child-Pugh classification was used to determine people who were candidates for a liver transplant.[102] Child-Pugh class B is usually an indication for evaluation for transplant.[104] However, there were many issues when applying this score to liver transplant eligibility.[102] Thus, the MELD score was created.

The Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score was later developed and approved in 2002.[105] It was approved by the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) as a way to determine the allocation of liver transplants to awaiting people in the United States.[106] It is also used as a validated survival predictor of cirrhosis, alcoholic hepatitis, acute liver failure, and acute hepatitis.[107] The variables included bilirubin, INR, creatinine, and dialysis frequency.[107] In 2016, sodium was added to the variables and the score is often referred to as MELD-Na.[108]

MELD-Plus is a further risk score to assess severity of chronic liver disease. It was developed in 2017 as a result of a collaboration between Massachusetts General Hospital and IBM.[109] Nine variables were identified as effective predictors for 90-day mortality after a discharge from a cirrhosis-related hospital admission.[109] The variables include all Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD)'s components, as well as sodium, albumin, total cholesterol, white blood cell count, age, and length of stay.[109]

The hepatic venous pressure gradient (difference in venous pressure between incoming and outgoing blood to the liver) also determines the severity of cirrhosis, although it is hard to measure. A value of 16 mm or more means a greatly increased risk of death.[110][unreliable medical source?]

Prevention

[edit]Key prevention strategies for cirrhosis are population-wide interventions to reduce alcohol intake (through pricing strategies, public health campaigns, and personal counseling), programs to reduce the transmission of viral hepatitis, and screening of relatives of people with hereditary liver diseases.[111]

Little is known about factors affecting cirrhosis risk and progression. However, many studies have provided increasing evidence for the protective effects of coffee consumption against the progression of liver disease. These effects are more noticeable in liver disease that is associated with alcohol use disorder. Coffee has antioxidant and antifibrotic effects. Caffeine may not be the important component; polyphenols may be more important. Drinking two or more cups of coffee a day is associated with improvements in the liver enzymes ALT, AST, and GGT. Even in those with liver disease, coffee consumption can lower fibrosis and cirrhosis.[112]

Treatment

[edit]Generally, liver damage from cirrhosis cannot be reversed, but treatment can stop or delay further progression and reduce complications. A healthy diet is encouraged, as cirrhosis may be an energy-consuming process. A recommended diet consists of high-protein, high-fiber diet plus supplementation with branched-chain amino acids.[113] Close follow-up is often necessary. Antibiotics are prescribed for infections, and various medications can help with itching. Laxatives, such as lactulose, decrease the risk of constipation. Carvedilol increases survival benefit for people with cirrhosis and portal hypertension.[114] Diuretics in combination with low salt diet reduce fluid in body which helps reduce oedema.[115]

Alcoholic cirrhosis caused by alcohol use disorder is treated by abstaining from alcohol. Treatment for hepatitis-related cirrhosis involves medications used to treat the different types of hepatitis, such as interferon for viral hepatitis and corticosteroids for autoimmune hepatitis.[citation needed]

Cirrhosis caused by Wilson's disease is treated by removing the copper which builds up in organs.[2] This is carried out using chelation therapy such as penicillamine. When the cause is an iron overload, iron is removed using a chelation agent such as deferoxamine or by bloodletting.[citation needed]

As of 2021, there are recent studies studying drugs to prevent cirrhosis caused by non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD or NASH). The drug semaglutide was shown to provide greater NASH resolution versus placebo. No improvement in fibrosis was observed.[116] A combination of cilofexor/firsocostat was studied in people with bridging fibrosis and cirrhosis. It was observed to have led to improvements in NASH activity with a potential antifibrotic effect.[117] Lanifibranor is also shown to prevent worsening fibrosis.[118]

Preventing further liver damage

[edit]Regardless of the underlying cause of cirrhosis, consumption of alcohol and other potentially damaging substances is discouraged. There is no evidence that supports the avoidance or dose reduction of paracetamol in people with compensated cirrhosis; it is thus considered a safe analgesic for said individuals.[119]

Vaccination against hepatitis A and hepatitis B is recommended early in the course of illness due to decline in effectiveness of the vaccines with decompensation.[120]

Treating the cause of cirrhosis prevents further damage; for example, giving oral antivirals such as entecavir and tenofovir where cirrhosis is due to hepatitis B prevents progression of cirrhosis. Similarly, control of weight and diabetes prevents deterioration in cirrhosis due to non-alcoholic fatty liver disease.[121]

People with cirrhosis or liver damage are often advised to avoid drugs that could further harm the liver.[122] These include several drugs such as anti-depressants, certain antibiotics, and NSAIDs (like ibuprofen).[122] These agents are hepatotoxic as they are metabolized by the liver. If a medication that harms the liver is still recommended by a doctor, the dosage can be adjusted to aim for minimal stress on the liver.[citation needed]

Lifestyle

[edit]According to a 2018 systematic review based on studies that implemented 8 to 14 week-long exercise programs, there is currently insufficient scientific evidence regarding either the beneficial or harmful effects of physical exercise in people with cirrhosis on all-cause mortality, morbidity (including both serious and non-serious adverse events), health-related quality of life, exercise capacity and anthropomorphic measures.[123] These conclusions were based on low to very low quality research, which imposes the need to develop further research with higher quality, especially to evaluate its effects on clinical outcomes.[citation needed]

Transplantation

[edit]If complications cannot be controlled or when the liver ceases functioning, liver transplantation is necessary. Survival from liver transplantation has been improving over the 1990s, and the five-year survival rate is now around 80%. The survival rate depends largely on the severity of disease and other medical risk factors in the recipient.[124] In the United States, the MELD score is used to prioritize patients for transplantation.[125] Transplantation necessitates the use of immune suppressants (ciclosporin or tacrolimus).

Decompensated cirrhosis

[edit]Manifestations of decompensation in cirrhosis include gastrointestinal bleeding, hepatic encephalopathy, jaundice or ascites. In patients with previously stable cirrhosis, decompensation may occur due to various causes, such as constipation, infection (of any source), increased alcohol intake, medication, bleeding from esophageal varices or dehydration. It may take the form of any of the complications of cirrhosis listed below.

People with decompensated cirrhosis generally require admission to a hospital, with close monitoring of the fluid balance, mental status, and emphasis on adequate nutrition and medical treatment – often with diuretics, antibiotics, laxatives or enemas, thiamine and occasionally steroids, acetylcysteine and pentoxifylline.[126] Administration of saline is avoided, as it would add to the already high total body sodium content that typically occurs in cirrhosis. Life expectancy without liver transplant is low, at most three years.

Palliative care

[edit]Palliative care is specialized medical care that focuses on providing patients with relief from the symptoms, pain, and stress of a serious illness, such as cirrhosis. The goal of palliative care is to improve quality of life for both the patient and the patient's family and it is appropriate at any stage and for any type of cirrhosis.[127]

Especially in the later stages, people with cirrhosis experience significant symptoms such as abdominal swelling, itching, leg edema, and chronic abdominal pain which would be amenable for treatment through palliative care.[128] Because the disease is not curable without a transplant, palliative care can also help with discussions regarding the person's wishes concerning health care power of attorney, do not resuscitate decisions and life support, and potentially hospice.[128] Despite proven benefit, people with cirrhosis are rarely referred to palliative care.[129]

Immune system

[edit]Cirrhosis is known to cause immune dysfunction in numerous ways. It impedes the immune system from working normally.[130]

Bleeding and blood clot risk

[edit]Cirrhosis can increase the risk of bleeding. The liver produces various proteins in the coagulation cascade (coagulation factors II, VII, IX, X, V, and VI). When damaged, the liver is impaired in its production of these proteins.[131] This will ultimately increase bleeding as clotting factors are diminished. Clotting function is estimated by lab values, mainly platelet count, prothrombin time (PT), and international normalized ratio (INR).

The American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) provided recommendations in 2021 in regards to coagulopathy management of cirrhotic patients in certain scenarios.[131]

- The AGA does not recommend for extensive pre-procedural testing, including repeated measurements of PT/INR or platelet count before patients with stable cirrhosis undergo common gastrointestinal procedures. Nor do they suggest the routine use of blood products, such as platelets, for bleeding prevention.[131] Cirrhosis is stable when there are no changes in baseline abnormalities of coagulation lab values.

- For patients with stable cirrhosis and low platelet count undergoing common low-risk procedures, the AGA does not recommend the routine use of thrombopoietin receptor agonists for bleeding prevention.[131]

- In hospitalized patients who meet standard guidelines for clot prevention, the AGA suggests standard prevention.[131]

- The AGA does not recommend in routine screening for portal vein thrombosis. If there is a portal vein thrombosis, the AGA suggests treatment by anticoagulation.[131]

- In the case of cirrhosis with atrial fibrillation, the AGA recommends using anticoagulation over no anticoagulation.[131]

Complications

[edit]Ascites

[edit]Salt restriction is often necessary, as cirrhosis leads to accumulation of salt (sodium retention). Diuretics may be necessary to suppress ascites. Diuretic options for inpatient treatment include aldosterone antagonists (spironolactone) and loop diuretics. Aldosterone antagonists are preferred for people who can take oral medications and are not in need of an urgent volume reduction. Loop diuretics can be added as additional therapy.[132]

Where salt restriction and the use of diuretics are ineffective then paracentesis may be the preferred option.[133] This procedure requires the insertion of a plastic tube into the peritoneal cavity. Human serum albumin solution is usually given to prevent complications from the rapid volume reduction. In addition to being more rapid than diuretics, 4–5 liters of paracentesis is more successful in comparison to diuretic therapy.[132]

Esophageal and gastric variceal bleeding

[edit]For portal hypertension, nonselective beta blockers such as propranolol or nadolol are commonly used to lower blood pressure over the portal system. In severe complications from portal hypertension, transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunting (TIPS) is occasionally indicated to relieve pressure on the portal vein. As this shunting can worsen hepatic encephalopathy, it is reserved for those patients at low risk of encephalopathy. TIPS is generally regarded only as a bridge to liver transplantation[134] or as a palliative measure.[citation needed] Balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration can be used to treat gastric variceal bleeding.[135]

Gastroscopy (endoscopic examination of the esophagus, stomach, and duodenum) is performed in cases of established cirrhosis. If esophageal varices are found, prophylactic local therapy may be applied such as sclerotherapy or banding, and beta blockers may be used.[136][137][138]

Hepatic encephalopathy

[edit]Hepatic encephalopathy is a potential complication of cirrhosis.[33] It may lead to functional neurological impairment ranging from mild confusion to coma.[33] Hepatic encephalopathy is primarily caused by the accumulation of ammonia in the blood, which causes neurotoxicity when crossing the blood-brain barrier. Ammonia is normally metabolized by the liver; as cirrhosis causes both decreased liver function and increased portosystemic shunting (allowing blood to bypass the liver), systemic ammonia levels gradually rise and lead to encephalopathy.[139]

Most pharmaceutical approaches to treating hepatic encephalopathy focus on reducing ammonia levels.[140] Per 2014 guidelines,[141] the first-line treatment involves the use of lactulose, a non-absorbable disaccharide which decreases the pH level of the colon when it is metabolized by intestinal bacteria. The lower colonic pH causes increased conversion of ammonia into ammonium, which is then excreted from the body.[142] Rifaximin, an antibiotic that inhibits the function of ammonia-producing bacteria in the gastrointestinal tract,[143] is recommended for use in combination with lactulose as prophylaxis against recurrent episodes of hepatic encephalopathy.[141][144][145]

In addition to pharmacotherapy, providing proper hydration and nutritional support is also essential.[140] Appropriate quantities of protein uptake is encouraged.[146] Several factors may precipitate hepatic encephalopathy, which include alcohol use, excess protein, gastrointestinal bleeding, infection, constipation, and vomiting/diarrhea.[140] Drugs such as benzodiazepines, diuretics, or narcotics can also precipitate encephalopathic events.[140] A low protein diet is recommended with gastrointestinal bleeding.[146]

The severity of hepatic encephalopathy is determined by assessing the patient's mental status. This is generally a subjective assessment, although several attempts at creating criteria to help standardize this assessment have been published. One example is the West Haven criteria, reproduced below.

| Grade | Mental status |

| Grade 1: Mild | Changes in behavior |

| Mild confusion | |

| Slurred speech | |

| Disordered sleep | |

| Grade 2: Moderate | Lethargy |

| Moderate confusion | |

| Grade 3: Severe | Stupor |

| Incoherent | |

| Sleeping but arousable | |

| Grade 4: Coma | Coma/Unresponsive |

People with cirrhosis have a 40% lifetime risk of developing hepatic encephalopathy.[59] The median survival after the development of hepatic encephalopathy is 0.9 years.[59] Mild hepatic encephalopathy (also known as covert hepatic encephalopathy), in which symptoms are more subtle, such as impairments in executive function, poor sleep or balance impairment is also associated with a higher risk of hospitalization and death (18% in those with covert hepatic encephalopathy vs 3% in those with cirrhosis and no HE).[59]

Hepatorenal syndrome

[edit]Hepatorenal syndrome is a serious complication of end-stage cirrhosis when kidney damage is also involved.[148] The annual risk of developing hepatorenal syndrome in those with cirrhosis is 8% and once the syndrome develops the median survival is 2 weeks.[59]

Portal hypertensive gastropathy

[edit]Portal hypertensive gastropathy refers to changes in the mucosa of the stomach in people with portal hypertension, and is associated with cirrhosis severity.[149]

Infection

[edit]Cirrhosis can cause immune system dysfunction, leading to infection. Signs and symptoms of infection may be nonspecific and are more difficult to recognize (for example, worsening encephalopathy but no fever).[150] Moreover, infections in cirrhosis are major triggers for other complications (ascites, variceal bleeding, hepatic encephalopathy, organ failures, death).[150][88][90]

Those with cirrhosis are at increased risk of infections as well as increased mortality from infections. This is due to a combination of factors including cirrhosis associated immune dysfunction, reduced gut barrier function, reduced bile flow, and changes in the gut microbiota, with an increase in pathobionts (native bacteria, that under certain conditions may cause infection).[130]

Cirrhosis associated immune dysfunction is caused by reduced complement component synthesis in the liver including C3, C4 and reduced total complement activity (CH50).[130] The complement system is a part of the innate immune system and assists immune cells and antibodies in destroying pathogens. The liver produces compliment factors, but this may be reduced in cirrhosis, raising the risk of infections. Acute phase proteins (which help mount an immune response) and soluble pattern recognition receptors (which help immune cells to identify pathogens) are also reduced in those with cirrhosis, leading to further immune dysfunction.[130] Cirrhosis is also associated with reduced Kupfer cell function, further increasing the risk for infections. Kupfer cells are resident macrophages in the liver which help to destroy pathogens.[130]

Extrinsic factors may also increase the risk of infection in those with cirrhosis, including proton pump inhibitor use, alcohol use, frailty, antibiotic overuse, and hospitalizations or invasive procedures (which increase the risk of bacterial translocation to other areas of the body).[130]

Infections that are common in those in the hospital with cirrhosis include spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (with a prevalence of 27% among hospitalized patients), urinary tract infections (22-29%), pneumonia (19%), spontaneous bacteremia (8-13%), skin and soft tissue infections (8-12%) and C. difficile colitis (2.4-4%).[130][151] It is estimated that 3.5% of people with cirrhosis and ascites may have asymptomatic spontaneous bacterial peritonitis.[152]

The mortality rate for infections in those with cirrhosis is higher than that of the general population. In those with cirrhosis and severe infections with sepsis the mortality rate is greater than 50% and in those with septic shock, the mortality rate is 65%.[130]

Hepatocellular carcinoma

[edit]Hepatocellular carcinoma is the most common primary liver cancer, and the most common cause of death in people with cirrhosis.[153] Screening using an ultrasound with or without cancer markers such as alpha-fetoprotein can detect this cancer and is often carried out for early signs which has been shown to improve outcomes.[2][154]

Epidemiology

[edit]

Each year, approximately one million deaths are due to complications of cirrhosis, making cirrhosis the 11th most common cause of death globally.[156] Cirrhosis and chronic liver disease were the tenth leading cause of death for men and the twelfth for women in the United States in 2001, killing about 27,000 people each year.[157]

The cause of cirrhosis can vary; alcohol and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease are main causes in western and industrialized countries, whereas viral hepatitis is the predominant cause in low and middle-income countries.[156] Cirrhosis is more common in men than in women.[158] The cost of cirrhosis in terms of human suffering, hospital costs, and lost productivity is high.

Globally, age-standardized disability-adjusted life year (DALY) rates have decreased from 1990 to 2017, with the values going from 656.4 years per 100,000 people to 510.7 years per 100,000 people.[159] In males DALY rates have decreased from 903.1 years per 100,000 population in 1990, to 719.3 years per 100,000 population in 2017; in females the DALY rates have decreased from 415.5 years per 100,000 population in 1990, to 307.6 years per 100,000 population in 2017.[159] However, globally the total number of DALYs have increased by 10.9 million from 1990 to 2017, reaching the value of 41.4 million DALYs.[159]

Etymology

[edit]The word "cirrhosis" is a neologism derived from Greek: κίρρωσις; kirrhos κιρρός, meaning "yellowish, tawny" (the orange yellow colour of the diseased liver) and the suffix -osis, i.e. "condition" in medical terminology.[160][161][162] While the clinical entity was known before, René Laennec gave it this name in an 1819 paper.[26]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p "Cirrhosis". National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. April 23, 2014. Archived from the original on 9 June 2015. Retrieved 19 May 2015.

- ^ a b c d e Ferri FF (2019). Ferri's clinical advisor 2019 : 5 books in 1. Philadelphia, PA. pp. 337–339. ISBN 978-0-323-53042-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b "Treatment for Cirrhosis | NIDDK". National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Archived from the original on 20 March 2021. Retrieved 6 March 2021.

- ^ a b Vos T, Allen C, Arora M, Barber RM, Bhutta ZA, Brown A, et al. (October 2016). "Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". Lancet. 388 (10053): 1545–1602. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31678-6. PMC 5055577. PMID 27733282.

- ^ a b c Wang H, Naghavi M, Allen C, Barber RM, Bhutta ZA, Carter A, et al. (GBD 2015 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators) (October 2016). "Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". Lancet. 388 (10053): 1459–1544. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(16)31012-1. PMC 5388903. PMID 27733281.

- ^ a b c "Cirrhosis". nhs.uk. 29 June 2020. Archived from the original on 5 October 2017. Retrieved 16 July 2024.

- ^ Tsochatzis EA, Bosch J, Burroughs AK (2014). "Liver cirrhosis". The Lancet. 383 (9930): 1749–1761. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60121-5. PMID 24480518.

- ^ Sharma B, John S (31 October 2022). "Hepatic Cirrhosis". StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island, Florida: StatPearls Publishing. PMID 29494026. Bookshelf ID NBK482419. Retrieved 16 July 2024 – via National Library of Medicine.

- ^ a b c Bansal MB, Friedman SL (8 June 2018). "Chapter 6: Hepatic Fibrinogenesis". In Dooley JS, Lok AS, Garcia-Tsao G, Pinzani M (eds.). Sherlock's diseases of the liver and biliary system (13th ed.). Hoboken, New Jersey: Wiley Blackwell. pp. 82–92. ISBN 978-1-119-23756-3. OCLC 1019837000.

- ^ Haep N, Florentino RM, Squires JE, Bell A, Soto-Gutierrez A (2021). "The Inside-Out of End-Stage Liver Disease: Hepatocytes are the Keystone". Seminars in Liver Disease. 41 (2): 213–224. doi:10.1055/s-0041-1725023. PMC 8996333. PMID 33992030.

- ^ a b "Cirrhosis of the liver". cleveland clinic. 2024.

- ^ McCormick PA, Jalan R (8 June 2018). "Chapter 8: Hepatic Cirrhosis". In Dooley JS, Lok AS, Garcia-Tsao G, Pinzani M (eds.). Sherlock's diseases of the liver and biliary system (13th ed.). Hoboken, New Jersey: Wiley Blackwell. pp. 107–126. ISBN 978-1-119-23756-3. OCLC 1019837000.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "Symptoms & Causes of Cirrhosis | NIDDK". National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Archived from the original on 8 February 2021. Retrieved 8 February 2021.

- ^ "Definition & Facts for Cirrhosis | NIDDK". National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Archived from the original on 2021-03-11. Retrieved 2021-03-10.

- ^ Rinella ME, Lazarus JV, Ratziu V, Francque SM, Sanyal AJ, Kanwal F, et al. (2024). "A multisociety Delphi consensus statement on new fatty liver disease nomenclature". Annals of Hepatology. 29 (1). doi:10.1016/j.aohep.2023.101133. hdl:2434/1050088. PMID 37364816. Art. No. 101133.

- ^ a b Castera L, Friedrich-Rust M, Loomba R (April 2019). "Noninvasive Assessment of Liver Disease in Patients With Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease". Gastroenterology. 156 (5): 1264–1281.e4. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2018.12.036. PMC 7505052. PMID 30660725.

- ^ Ilić G, Karadžić R, Kostić-Banović L, Stojanović J, Antović A (February 2010). "Ultrastructural Changes In The Liver Of Intravenous Heroin Addiction". Bosnian Journal of Basic Medical Sciences. Vol. 10, no. 1. Journal of the Association of Basic Medical Sciences. pp. 36–43. PMC 5596609.

- ^ Naghavi M, Wang H, Lozano R, Davis A, Liang X, Zhou M, et al. (GBD 2013 Mortality Causes of Death Collaborators) (January 2015). "Global, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013". Lancet. 385 (9963): 117–171. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61682-2. PMC 4340604. PMID 25530442.

- ^ "Alcoholic liver disease". MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 2019-05-27. Retrieved 2021-03-10.

- ^ "Heroin and Liver Damage". Banyan Medical Centers. Retrieved August 7, 2022.

- ^ a b "Definition & Facts of NAFLD & NASH | NIDDK". National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Archived from the original on 12 March 2021. Retrieved 9 March 2021.

- ^ Grady J (15 February 2024). "Back to Basics: Outpatient Management of Cirrhosis". Liver Fellow Network. American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Retrieved 16 July 2024.

- ^ Singal AG, Llovet JM, Yarchoan M, Mehta N, Heimbach JK, Dawson LA, et al. (2023). "AASLD Practice Guidance on prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma". Hepatology. 78 (6): 1922–1965. doi:10.1097/HEP.0000000000000466. PMC 10663390. PMID 37199193.

- ^ Liao Z, Tang C, Luo R, Gu X, Zhou J, Gao J (2023). "Current Concepts of Precancerous Lesions of Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Recent Progress in Diagnosis". Diagnostics. 13 (7): 1211. doi:10.3390/diagnostics13071211. PMC 10093043. PMID 37046429. Art. No. 1211.

- ^ Brower ST (2012). Elective general surgery : an evidence-based approach. New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. p. 36. ISBN 978-1-60795-109-4. Archived from the original on 2017-09-08.

- ^ a b Roguin A (September 2006). "Rene Theophile Hyacinthe Laënnec (1781-1826): the man behind the stethoscope". Clinical Medicine & Research. 4 (3): 230–235. doi:10.3121/cmr.4.3.230. PMC 1570491. PMID 17048358.

- ^ Bhandari K, Kapoor D (2022-03-01). "Fatigue in Cirrhosis". Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hepatology. 12 (2): 617–624. doi:10.1016/j.jceh.2021.08.028. ISSN 0973-6883. PMC 9077229. PMID 35535102.

- ^ Williams CN, Sidorov JJ (2024). "Steatorrhea in patients with liver disease". Canadian Medical Association Journal. 105 (11): 1143–1154. PMC 1931370. PMID 5150072.

- ^ a b c Samant H, Kothadia JP (2022). "Spider Angioma". StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. PMID 29939595. Retrieved 2022-03-14.

- ^ Kur P, Kolasa-Wołosiuk A, Misiakiewicz-Has K, Wiszniewska B (April 2020). "Sex Hormone-Dependent Physiology and Diseases of Liver". International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 17 (8): E2620. doi:10.3390/ijerph17082620. PMC 7216036. PMID 32290381.

- ^ Serrao R, Zirwas M, English JC (2007). "Palmar erythema". American Journal of Clinical Dermatology. 8 (6): 347–56. doi:10.2165/00128071-200708060-00004. PMID 18039017. S2CID 33297418.

- ^ Feingold KR, Anawalt B, Boyce A, Chrousos G, de Herder WW, Dhatariya K, et al. (2000). "Gynecomastia: Etiology, Diagnosis, and Treatment". In Feingold KR, Anawalt B, Boyce A, Chrousos G (eds.). Endotext. South Dartmouth (MA): MDText.com, Inc. PMID 25905330. Retrieved 2022-03-16.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u Longo DL, Fauci AS, Kasper DL, Hauser SL, Jameson JL, Loscalzo J, eds. (2012). Harrison's principles of internal medicine (18th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. pp. Chapter 308. Cirrhosis and Its Complications. ISBN 978-0-07-174889-6.

- ^ Kim SM, Yalamanchi S, Dobs AS (2017). "Male Hypogonadism and Liver Disease". In Winters SJ, Huhtaniemi IT (eds.). Male Hypogonadism. Cham: Springer International Publishing. pp. 219–234. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-53298-1_11. ISBN 978-3-319-53296-7.

- ^ Qi X, An S, Li H, Guo X (2017-08-24). "Recurrent scrotal edema in liver cirrhosis". AME Medical Journal. 2: 124. doi:10.21037/amj.2017.08.22.

- ^ Plauth M, Schütz ET (September 2002). "Cachexia in liver cirrhosis". International Journal of Cardiology. 85 (1): 83–87. doi:10.1016/s0167-5273(02)00236-x. PMID 12163212.

- ^ Jeffrey G (7 October 2021). "Cirrhosis of the Liver". emedicinehealth. Retrieved 15 March 2022.

- ^ "Jaundice - Hepatic and Biliary Disorders". Merck Manuals Professional Edition. Retrieved 2022-03-16.

- ^ a b c "Portal Hypertension". www.hopkinsmedicine.org. Retrieved 2022-03-16.

- ^ a b "Diagnosis of NAFLD & NASH | NIDDK". National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Archived from the original on 4 March 2021. Retrieved 9 March 2021.

- ^ a b Meseeha M, Attia M (2022). "Esophageal Varices". StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. PMID 28846255. Retrieved 2022-03-16.

- ^ a b Masoodi I, Farooq O, Singh R, Ahmad N, Bhat M, Wani A (January 2009). "Courveilhier baumgarten syndrome: a rare syndrome revisited". International Journal of Health Sciences. 3 (1): 97–99. PMC 3068787. PMID 21475517.

- ^ Witkowska AB, Jasterzbski TJ, Schwartz RA (2017). "Terry's Nails: A Sign of Systemic Disease". Indian Journal of Dermatology. 62 (3): 309–311. doi:10.4103/ijd.IJD_98_17. PMC 5448267. PMID 28584375.

- ^ Abd El Meged MM (2019-04-01). "Patterns of nail changes in chronic liver diseases". Sohag Medical Journal. 23 (2): 166–170. doi:10.21608/smj.2019.47672. ISSN 1687-8353. S2CID 203813520.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v Friedman L (2018). Handbook of Liver Disease, 4e. Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-323-47874-8.

- ^ Brennan D. "What Is Fetor Hepaticus?". WebMD. Retrieved 2022-03-17.

- ^ Alabama Jennifer A. Gentile, PharmD Candidate 2021 Logan B. Boone, PharmD Candidate 2021 Samford University McWhorter School of Pharmacy Birmingham, Alabama Jeffrey A. Kyle, PharmD, BCPS Professor of Pharmacy Practice Samford University McWhorter School of Pharmacy Birmingham, Alabama Langley R. Kyle, PharmD Clinical Pharmacy Specialist RxBenefits Birmingham. "Drug Considerations for Medication Therapy in Cirrhosis". www.uspharmacist.com. Retrieved 2024-11-08.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Samji NS, Buggs AM, Roy PK (2021-10-17). Anand BS (ed.). "Viral Hepatitis: Background, Pathophysiology, Etiology". Medscape. WebMD LLC.

- ^ a b Perz JF, Armstrong GL, Farrington LA, Hutin YJ, Bell BP (October 2006). "The contributions of hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus infections to cirrhosis and primary liver cancer worldwide". Journal of Hepatology. 45 (4): 529–538. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2006.05.013. PMID 16879891.

- ^ "Cirrhosis of the Liver". American Liver Foundation. Retrieved 2022-03-17.

- ^ a b Stickel F, Datz C, Hampe J, Bataller R (March 2017). "Pathophysiology and Management of Alcoholic Liver Disease: Update 2016". Gut and Liver. 11 (2): 173–188. doi:10.5009/gnl16477. PMC 5347641. PMID 28274107.

- ^ a b c Friedman LS (2014). Current medical diagnosis and treatment 2014. [S.l.]: Mcgraw-Hill. pp. Chapter 16. Liver, Biliary Tract, & Pancreas Disorders. ISBN 978-0-07-180633-6.

- ^ a b c d e Machado MV, Diehl AM (2018). "Pathogenesis of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease". In Sanyal AJ, Boyer TD, Terrault NA, Lindor KD (eds.). Zakim and Boyer's Hepatology. pp. 369–390. doi:10.1016/c2013-0-19055-1. ISBN 978-0-323-37591-7.

- ^ Golabi P, Paik JM, Arshad T, Younossi Y, Mishra A, Younossi ZM (August 2020). "Mortality of NAFLD According to the Body Composition and Presence of Metabolic Abnormalities". Hepatology Communications. 4 (8): 1136–1148. doi:10.1002/hep4.1534. PMC 7395070. PMID 32766474.

- ^ "Heroin Addiction Health Conditions". Bedrock Recovery Center. Retrieved August 7, 2022.

- ^ a b c "Primary Biliary Cholangitis: Symptoms, Causes, Treatments". Cleveland Clinic. Retrieved 2022-03-17.

- ^ Coenen IC, Houwen RH (January 2019). "Indian childhood cirrhosis and other disorders of copper handling.". Clinical and Translational Perspectives on Wiloson Disease. Academic Press. pp. 449–453. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-810532-0.00044-6. ISBN 978-0-12-810532-0. S2CID 80994882.

- ^ Oiseth S, Jones L, Maza E. "Galactosemia". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. Retrieved 15 August 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Tapper EB, Parikh ND (9 May 2023). "Diagnosis and Management of Cirrhosis and Its Complications: A Review". JAMA. 329 (18): 1589–1602. doi:10.1001/jama.2023.5997. PMC 10843851. PMID 37159031.

- ^ Hammer GD, McPhee SJ, eds. (2010). Pathophysiology of disease : an introduction to clinical medicine (6th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. pp. Chapter 14: Liver Disease. Cirrhosis. ISBN 978-0-07-162167-0.

- ^ Hassan S, Shah H, Shawana S (2020). "Dysregulated epidermal growth factor and tumor growth factor-beta receptor signaling through GFAP-ACTA2 protein interaction in liver fibrosis". Pakistan Journal of Medical Sciences. 36 (4): 782–787. doi:10.12669/pjms.36.4.1845. PMC 7260937. PMID 32494274.

- ^ Iredale JP (July 2003). "Cirrhosis: new research provides a basis for rational and targeted treatments". BMJ. 327 (7407): 143–147. doi:10.1136/bmj.327.7407.143. PMC 1126509. PMID 12869458. Archived from the original on 2004-10-29.

- ^ Puche JE, Saiman Y, Friedman SL (October 2013). "Hepatic stellate cells and liver fibrosis". Comprehensive Physiology. 3 (4): 1473–1492. doi:10.1002/cphy.c120035. ISBN 978-0-470-65071-4. PMID 24265236.

- ^ Wu M, Sharma PG, Grajo JR (September 2020). "The Echogenic Liver: Steatosis and Beyond". Ultrasound Quarterly. 37 (4): 308–314. doi:10.1097/RUQ.0000000000000510. PMID 32956242. S2CID 221842327.

- ^ Costantino A, Piagnani A, Nandi N, Sciola V, Maggioni M, Donato F, et al. (2022). "Reproducibility and diagnostic accuracy of pocket-sized ultrasound devices in ruling out compensated cirrhosis of mixed etiology". European Radiology. 32 (7): 4609–4615. doi:10.1007/s00330-022-08572-2. PMC 9213370. PMID 35238968.

- ^ Yeom SK, Lee CH, Cha SH, Park CM (August 2015). "Prediction of liver cirrhosis, using diagnostic imaging tools". World Journal of Hepatology. 7 (17): 2069–2079. doi:10.4254/wjh.v7.i17.2069. PMC 4539400. PMID 26301049.

- ^ Chapman J, Goyal A, Azevedo AM. Splenomegaly. [Updated 2021 Aug 11]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan-. Available from: [1]

- ^ a b c d Iranpour P, Lall C, Houshyar R, Helmy M, Yang A, Choi JI, et al. (January 2016). "Altered Doppler flow patterns in cirrhosis patients: an overview". Ultrasonography. 35 (1): 3–12. doi:10.14366/usg.15020. PMC 4701371. PMID 26169079.

- ^ Berzigotti A, Seijo S, Reverter E, Bosch J (February 2013). "Assessing portal hypertension in liver diseases". Expert Review of Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 7 (2): 141–155. doi:10.1586/egh.12.83. PMID 23363263. S2CID 31057915.

- ^ a b Goncalvesova E, Varga I, Tavacova M, Lesny P (2013). "Changes of portal vein flow in heart failure patients with liver congestion". European Heart Journal. 34 (suppl 1): 627. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/eht307.P627. ISSN 0195-668X.

- ^ a b Dietrich CF (2009). "Ultrasonography". In Dancygier H (ed.). Clinical Hepatology: Principles and Practice of Hepatobiliary Diseases. Vol. 1. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 367. ISBN 978-3-540-93842-2. Archived from the original on 2018-11-30.

- ^ Costantino A, Piagnani A, Nandi N, Sciola V, Maggioni M, Donato F, Vecchi M, Lampertico P, Casazza G, Fraquelli M. Reproducibility and diagnostic accuracy of pocket-sized ultrasound devices in ruling out compensated cirrhosis of mixed etiology. Eur Radiol. 2022 Jul;32(7):4609-4615. doi: 10.1007/s00330-022-08572-2. Epub 2022 Mar 3. PMID: 35238968; PMCID: PMC9213370.

- ^ "Elastography: MedlinePlus Medical Test". medlineplus.gov. Retrieved 2022-03-21.

- ^ Barr RG, Ferraioli G, Palmeri ML, Goodman ZD, Garcia-Tsao G, Rubin J, et al. (September 2015). "Elastography Assessment of Liver Fibrosis: Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound Consensus Conference Statement". Radiology. 276 (3): 845–861. doi:10.1148/radiol.2015150619. PMID 26079489.

- ^ Srinivasa Babu A, Wells ML, Teytelboym OM, Mackey JE, Miller FH, Yeh BM, et al. (2016-11-01). "Elastography in Chronic Liver Disease: Modalities, Techniques, Limitations, and Future Directions". Radiographics. 36 (7): 1987–2006. doi:10.1148/rg.2016160042. PMC 5584553. PMID 27689833.

- ^ a b Foucher J, Chanteloup E, Vergniol J, Castéra L, Le Bail B, Adhoute X, et al. (March 2006). "Diagnosis of cirrhosis by transient elastography (FibroScan): a prospective study". Gut. 55 (3): 403–408. doi:10.1136/gut.2005.069153. PMC 1856085. PMID 16020491.

- ^ Pavlov CS, Casazza G, Nikolova D, Tsochatzis E, Burroughs AK, Ivashkin VT, et al. (January 2015). "Transient elastography for diagnosis of stages of hepatic fibrosis and cirrhosis in people with alcoholic liver disease". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 1 (1): CD010542. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd010542.pub2. PMC 7081746. PMID 25612182.

- ^ Udell JA, Wang CS, Tinmouth J, FitzGerald JM, Ayas NT, Simel DL, et al. (February 2012). "Does this patient with liver disease have cirrhosis?". JAMA. 307 (8): 832–842. doi:10.1001/jama.2012.186. PMID 22357834.

- ^ Gudowska M, Gruszewska E, Panasiuk A, Cylwik B, Świderska M, Flisiak R, et al. (February 2016). "Selected Noninvasive Markers in Diagnosing Liver Diseases". Laboratory Medicine. 47 (1): 67–72. doi:10.1093/labmed/lmv015. PMID 26715612.

- ^ a b Maddrey WC, Schiff ER, Sorrell MF, eds. (1999). Schiff's diseases of the liver (11th ed.). Chichester, West Sussex, UK: John Wiley & Sons. pp. Evaluation of the Liver A: Laboratory Test. ISBN 978-0-470-65468-2.

- ^ Slater JS, Esherick DS, Clark ED (2012-12-18). Current practice guidelines in primary care 2013. New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. pp. Chapter 3: Disease Management. ISBN 978-0-07-179750-4.

- ^ Van Thiel DH, Gavaler JS, Schade RR (February 1985). "Liver disease and the hypothalamic pituitary gonadal axis". Seminars in Liver Disease. 5 (1): 35–45. doi:10.1055/s-2008-1041756. PMID 3983651. S2CID 35436861.

- ^ Halfon P, Munteanu M, Poynard T (September 2008). "FibroTest-ActiTest as a non-invasive marker of liver fibrosis". Gastroenterologie Clinique et Biologique. 32 (6 Suppl 1): 22–39. doi:10.1016/S0399-8320(08)73991-5. PMID 18973844.

- ^ Tornai D, Antal-Szalmas P, Tornai T, Papp M, Tornai I, Sipeki N, et al. (March 2021). "Abnormal ferritin levels predict development of poor outcomes in cirrhotic outpatients: a cohort study". BMC Gastroenterology. 21 (1): 94. doi:10.1186/s12876-021-01669-w. PMC 7923668. PMID 33653274.

- ^ Maiwall R, Kumar S, Chaudhary AK, Maras J, Wani Z, Kumar C, et al. (July 2014). "Serum ferritin predicts early mortality in patients with decompensated cirrhosis". Journal of Hepatology. 61 (1): 43–50. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2014.03.027. PMID 24681346.

- ^ a b c Papp M, Vitalis Z, Altorjay I, Tornai I, Udvardy M, Harsfalvi J, et al. (April 2012). "Acute phase proteins in the diagnosis and prediction of cirrhosis associated bacterial infections". Liver International. 32 (4): 603–611. doi:10.1111/j.1478-3231.2011.02689.x. PMID 22145664. S2CID 10326820. Archived from the original on 2021-04-25. Retrieved 2021-04-25.

- ^ Papp M, Tornai T, Vitalis Z, Tornai I, Tornai D, Dinya T, et al. (November 2016). "Presepsin teardown - pitfalls of biomarkers in the diagnosis and prognosis of bacterial infection in cirrhosis". World Journal of Gastroenterology. 22 (41): 9172–9185. doi:10.3748/wjg.v22.i41.9172. PMC 5107598. PMID 27895404.

- ^ a b Tornai T, Vitalis Z, Sipeki N, Dinya T, Tornai D, Antal-Szalmas P, et al. (November 2016). "Macrophage activation marker, soluble CD163, is an independent predictor of short-term mortality in patients with cirrhosis and bacterial infection". Liver International. 36 (11): 1628–1638. doi:10.1111/liv.13133. hdl:2437/223046. PMID 27031405. S2CID 206174528. Archived from the original on 2021-04-25. Retrieved 2021-04-25.

- ^ Laursen TL, Rødgaard-Hansen S, Møller HJ, Mortensen C, Karlsen S, Nielsen DT, et al. (April 2017). "The soluble mannose receptor is released from the liver in cirrhotic patients, but is not associated with bacterial translocation". Liver International. 37 (4): 569–575. doi:10.1111/liv.13262. PMID 27706896. S2CID 46856702.

- ^ a b Tornai D, Vitalis Z, Jonas A, Janka T, Foldi I, Tornai T, et al. (September 2021). "Increased sTREM-1 levels identify cirrhotic patients with bacterial infection and predict their 90-day mortality". Clinics and Research in Hepatology and Gastroenterology. 45 (5): 101579. doi:10.1016/j.clinre.2020.11.009. PMID 33773436.

- ^ Zhu X, Zhou Z, Pan X (2024-03-14). "Research reviews and prospects of gut microbiota in liver cirrhosis: a bibliometric analysis (2001–2023)". Frontiers in Microbiology. 15. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2024.1342356. ISSN 1664-302X. PMC 10972893. PMID 38550860.

- ^ Qin N, Yang F, Li A, Prifti E, Chen Y, Shao L, et al. (September 2014). "Alterations of the human gut microbiome in liver cirrhosis". Nature. 513 (7516): 59–64. Bibcode:2014Natur.513...59Q. doi:10.1038/nature13568. PMID 25079328. S2CID 205239766.

- ^ a b McCarty TR, Bazarbashi AN, Njei B, Ryou M, Aslanian HR, Muniraj T (September 2020). "Endoscopic Ultrasound-Guided, Percutaneous, and Transjugular Liver Biopsy: A Comparative Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". Clinical Endoscopy. 53 (5): 583–593. doi:10.5946/ce.2019.211. PMC 7548145. PMID 33027584.

- ^ a b Mok SR, Diehl DL (January 2019). "The Role of EUS in Liver Biopsy". Current Gastroenterology Reports. 21 (2): 6. doi:10.1007/s11894-019-0675-8. PMID 30706151. S2CID 73440352.

- ^ Diehl DL (April 2019). "Endoscopic Ultrasound-guided Liver Biopsy". Gastrointestinal Endoscopy Clinics of North America. 29 (2): 173–186. doi:10.1016/j.giec.2018.11.002. PMC 6383155. PMID 30846147.

- ^ Grant A, Neuberger J (October 1999). "Guidelines on the use of liver biopsy in clinical practice. British Society of Gastroenterology". Gut. 45 (Suppl 4): IV1 – IV11. doi:10.1136/gut.45.2008.iv1. PMC 1766696. PMID 10485854. Archived from the original on 2007-06-30.

The main cause of mortality after percutaneous liver biopsy is intraperitoneal haemorrhage as shown in a retrospective Italian study of 68,000 percutaneous liver biopsies, in which all six patients who died did so from intraperitoneal haemorrhage. Three of these patients had had a laparotomy, and all had either cirrhosis or malignant disease, both of which are risk factors for bleeding.

- ^ a b c Brenner D, Rippe RA (2003). "Pathogenesis of Hepatic Fibrosis". In Yamada (ed.). Textbook of Gastroenterology. Vol. 2 (4th ed.). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 978-0-7817-2861-4.

- ^ a b c d Boyd A, Cain O, Chauhan A, Webb GJ (2020). "Medical liver biopsy: background, indications, procedure and histopathology". Frontline Gastroenterology. 11 (1): 40–47. doi:10.1136/flgastro-2018-101139. ISSN 2041-4137. PMC 6914302. PMID 31885839.

-"This is an open access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Unported (CC BY 4.0) license" - ^ Giallourakis CC, Rosenberg PM, Friedman LS (November 2002). "The liver in heart failure". Clinics in Liver Disease. 6 (4): 947–67, viii–ix. doi:10.1016/S1089-3261(02)00056-9. PMID 12516201.

- ^ Heathcote EJ (November 2003). "Primary biliary cirrhosis: historical perspective". Clinics in Liver Disease. 7 (4): 735–740. doi:10.1016/S1089-3261(03)00098-9. PMID 14594128.

- ^ Bashar S, Savio J (2020). "Hepatic Cirrhosis". StatPearls. StatPearls. PMID 29494026. Archived from the original on 2020-09-03. Retrieved 2019-11-11.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Tsoris A, Marlar CA (2022). "Use Of The Child Pugh Score In Liver Disease". StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. PMID 31194448. Retrieved 2022-03-23.

- ^ Shakerdge K. "What Are the MELD and Child-Pugh Scores for Liver Disease?". WebMD. Retrieved 2022-03-23.

- ^ a b c d e "Child-Pugh Score for Cirrhosis Mortality". MDCalc. Retrieved 2022-03-23.

- ^ Singal AK, Kamath PS (March 2013). "Model for End-stage Liver Disease". Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hepatology. 3 (1): 50–60. doi:10.1016/j.jceh.2012.11.002. PMC 3940492. PMID 25755471.

- ^ Peng Y, Qi X, Guo X (February 2016). "Child-Pugh Versus MELD Score for the Assessment of Prognosis in Liver Cirrhosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies". Medicine. 95 (8): e2877. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000002877. PMC 4779019. PMID 26937922.

- ^ a b "MELD Score (Model For End-Stage Liver Disease) (12 and older)". MDCalc. Retrieved 2022-03-24.

- ^ "MELDNa/MELD-Na Score for Liver Cirrhosis". MDCalc. Retrieved 2022-03-24.

- ^ a b c Kartoun U, Corey KE, Simon TG, Zheng H, Aggarwal R, Ng K, et al. (2017). "The MELD-Plus: A generalizable prediction risk score in cirrhosis". PLOS ONE. 12 (10): e0186301. Bibcode:2017PLoSO..1286301K. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0186301. PMC 5656314. PMID 29069090.

- ^ Patch D, Armonis A, Sabin C, Christopoulou K, Greenslade L, McCormick A, et al. (February 1999). "Single portal pressure measurement predicts survival in cirrhotic patients with recent bleeding". Gut. 44 (2): 264–269. doi:10.1136/gut.44.2.264. PMC 1727391. PMID 9895388. Archived from the original on 2008-05-28.

- ^ "Cirrhosis". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. 28 September 2020. Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 9 July 2021.

- ^ Wadhawan M, Anand AC (March 2016). "Coffee and Liver Disease". Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hepatology. 6 (1): 40–46. doi:10.1016/j.jceh.2016.02.003. PMC 4862107. PMID 27194895.

- ^ Ruiz-Margáin A, Macías-Rodríguez RU, Ríos-Torres SL, Román-Calleja BM, Méndez-Guerrero O, Rodríguez-Córdova P, et al. (January 2018). "Effect of a high-protein, high-fiber diet plus supplementation with branched-chain amino acids on the nutritional status of patients with cirrhosis". Revista de Gastroenterologia de Mexico. 83 (1): 9–15. doi:10.1016/j.rgmx.2017.02.005. PMID 28408059. S2CID 196487820.

- ^ McDowell HR, Chuah CS, Tripathi D, Stanley AJ, Forrest EH, Hayes PC (February 2021). "Carvedilol is associated with improved survival in patients with cirrhosis: a long-term follow-up study". Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 53 (4): 531–539. doi:10.1111/apt.16189. hdl:20.500.11820/83f830e0-832f-401e-bfe3-5576d368ea15. PMID 33296526. S2CID 228089776.

- ^ "Treatment of Cirrhosis". NHS. 20 October 2017.

- ^ Newsome PN, Buchholtz K, Cusi K, Linder M, Okanoue T, Ratziu V, et al. (March 2021). "A Placebo-Controlled Trial of Subcutaneous Semaglutide in Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis". The New England Journal of Medicine. 384 (12): 1113–1124. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2028395. PMID 33185364. S2CID 226850568.

- ^ Loomba R, Noureddin M, Kowdley KV, Kohli A, Sheikh A, Neff G, et al. (February 2021). "Combination Therapies Including Cilofexor and Firsocostat for Bridging Fibrosis and Cirrhosis Attributable to NASH". Hepatology. 73 (2): 625–643. doi:10.1002/hep.31622. PMID 33169409. S2CID 226295213.

- ^ Francque SM, Bedossa P, Ratziu V, Anstee QM, Bugianesi E, Sanyal AJ, et al. (October 2021). "A Randomized, Controlled Trial of the Pan-PPAR Agonist Lanifibranor in NASH". The New England Journal of Medicine. 385 (17): 1547–1558. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2036205. hdl:1854/LU-8731444. PMID 34670042. S2CID 239051427.

- ^ Schweighardt AE, Juba KM (December 2018). "A Systematic Review of the Evidence Behind Use of Reduced Doses of Acetaminophen in Chronic Liver Disease". Journal of Pain & Palliative Care Pharmacotherapy. 32 (4): 226–239. doi:10.1080/15360288.2019.1611692. PMID 31206302. S2CID 190535151.

- ^ Bajaj JS, Kamath PS, Reddy KR (2021). "The Evolving Challenge of Infections in Cirrhosis". The New England Journal of Medicine. 384 (24): 2317–2330. doi:10.1056/NEJMra2021808. PMID 34133861.