Trekkie

A Trekkie (a portmanteau of "trek" and "junkie") or Trekker is a fan of the Star Trek franchise, or of specific television series or films within that franchise. The show developed a following shortly after it premiered, with the first fanzine premiering in 1967. The first fan convention took place the year the original series ended.

The degree of Trekkies' devotion has produced conflicted feelings among the cast and crew of the show. Creator Gene Roddenberry initially encouraged the fan participation, but over the years became concerned that some fans treated the show with a quasi-religious zeal as though it were "scripture." While some stars have been vocally critical of the franchise's most devoted fans, others including Sir Patrick Stewart have defended Trekkies.

There has been some disagreement within the fandom as to the distinction between the terms "Trekker" and "Trekkie." Some characterize Trekkers are "more serious" in comparison to the "bubble-headed" Trekkies, while others have chosen the term Trekker to convey that they are "a rational fan." Leonard Nimoy advocated for the use of "Trekker" over "Trekkie". Overall, the term "Trekkie" is more commonly used.

History

[edit]Many early Trekkies were also fans of The Man from U.N.C.L.E. (1964–1968), another show with science fiction elements and a devoted audience.[1] The first Star Trek fanzine, Spockanalia, appeared in September 1967, including the first published fan fiction based on the show. Star Trek creator Gene Roddenberry, who was aware of and encouraged such activities,[2]: 1 a year later estimated that 10,000 wrote or read fanzines.[3] The mainstream science fiction magazine If published a poem about the Star Trek character Spock, accompanying a Virgil Finlay portrait of the character.[4]

Perhaps the first large gathering of fans occurred in April 1967. When actor Leonard Nimoy appeared as Spock as grand marshal of the Medford Pear Blossom Festival parade in Oregon, he hoped to sign hundreds of autographs but thousands of people appeared; after being rescued by police, "I made sure never to appear publicly again in Vulcan guise", the actor wrote.[5][6] Another was in January 1968, when more than 200 Caltech students marched to NBC's Burbank, California studio to support Star Trek's renewal.[7]

The first fan convention devoted to the show occurred on 1 March 1969 at the Newark Public Library. Organized by a librarian who was one of the creators of Spockanalia, the "Star Trek Con" did not have celebrity guests but did have "slide shows of 'Trek' aliens, skits and a fan panel to discuss 'The Star Trek Phenomenon.'"[8]: 280–281 [9] Some fans were so devoted that they complained to a Canadian TV station when it preempted an episode in July 1969 for coverage of Apollo 11.[10]

Nothing fades faster than a canceled television series they say. So how come Star Trek won't go away?

However, the Trekkie phenomenon did not come to the attention of the general public until after the show was cancelled in 1969 and reruns entered syndication.[12] The first widely publicized fan convention occurred in January 1972 at the Statler Hilton Hotel in New York, featuring Roddenberry, Isaac Asimov, and two tons of NASA memorabilia. The organizers expected 500 attendees at the "First International Star Trek Convention" but more than 3,000 came;[13][2]: 9, 11 [14] attendees later described it as "packed" and like "a rush-hour subway train".[15] By then more than 100 fanzines about the show existed, its reruns were syndicated to 125 American TV stations and 60 other countries,[11] and news reports on the convention caused other fans, who had believed themselves to be alone, to organize.[12]

Some actors, such as Nichelle Nichols, were unaware of the size of the show's fandom until the conventions,[16] but major and minor cast members began attending them around the United States.[9][17][18] The conventions became so popular that the media cited Beatlemania and Trudeaumania as examples to describe the emerging "cultural phenomenon".[13][19] 6,000 attended the 1973 New York convention and 15,000 attended in 1974,[1] much larger figures than at older events like the 4,500 at the 32nd Worldcon in 1974.[2]: 16 By then the demand from Trekkies was large enough that rival convention organizers began to sue each other.[20] The first UK convention was held in 1974 and featured special guests George Takei and James Doohan. After this, there was an official British convention yearly.[21]

Turnout and security at the exhibition are unprecedented [with] alarm display cases and two full-time guards on hand to protect the memorabilia from overzealous fans.

Because Star Trek was set in the future the show did not become dated, and by counterprogramming during the late afternoon or early evening when other stations showed television news it attracted a young audience. The reruns' great popularity—greater than when Star Trek originally aired in prime time—caused Paramount to receive thousands of letters each week demanding the show's return and promising that it would be profitable.[12][23]: 91–92 [24][25] (The fans were correct; by the mid-1990s Star Trek—now called within Paramount "the franchise"[26] and its "crown jewel"[27]—had become the studio's single most-important property,[23]: 93 [28]: 49–50, 54 and Paramount sponsored its first convention in 1996.[29])

The entire cast reunited for the first time at an August 1975 Chicago convention that 16,000 attended.[24][30] "Star Trek" Lives!, an early history and exploration of Trekkie culture published that year, was the first mass-market book to introduce fan fiction and other aspects of fandom to a wide audience.[1][2]: viii, 8, 19, 20, 24, 27 By 1976 there were more than 250 Star Trek clubs, and at least three rival groups organized 25 conventions that attracted thousands to each.[31][20] While discussing that year whether to name the first Space Shuttle Enterprise, James M. Cannon, Gerald R. Ford's domestic policy advisor, described Trekkies as "one of the most dedicated constituencies in the country".[32] "Unprecedented" crowds visited a 1992 Star Trek exhibit at the Smithsonian Institution's National Air and Space Museum,[22] and in 1994, when Star Trek reruns still aired in 94% of the United States, over 400,000 attended 130 conventions.[33] By the late 1990s an estimated two million people in the United States, or about 5% of 35 million weekly Star Trek watchers, were what one author described as "hard-core fans".[28]: 139

The Trek fandom was notably fast to use the World Wide Web. The Guardian's Damien Walter joked that "the 50% of the early world wide web that wasn't porn was made up of Star Trek: The Next Generation fansites".[34]

Characteristics

[edit]

Stereotypes

[edit]There are some fans who have become overzealous. That can become terrible. They leap out of bushes, look in windows and lean against doors and listen.

— William Shatner, 1986[35]

Since only about a dozen quarterbacks are selected during the typical draft, a 64-quarterback draft board transcends "thorough" and reaches "fetishistic". This is the stuff of Star Trek conventions. In a few years, the football equivalent of "Mr. Shatner, why didn't the Enterprise use antimatter to destabilize the alien probe in the Tholian Web?" will be "Coach Coughlin, what do you think of Scott Buisson?"

— The New York Times, 2011[36]

In 1975, a journalist described Trekkies as "smelling of assembly-line junk food, hugely consumed; the look is of people who consume it, habitually and at length; overfed and undernourished, eruptive of skin and flaccid of form, from the merely soft to the grotesquely obese". He noted their fixation on one subject:[19]

The facial expression is a near sultry somnolence, except when matters of Star Trek textual minutiae are discussed; then it is as vivid and keen as a Jesuit Inquisitor's, for these people know more of the production details of Star Trek than Roddenberry, who created them, and are a greater authority on the essential mystery of Captain Kirk than [William] Shatner, who fleshed it out.

In December 1986, Shatner hosted an episode of Saturday Night Live. In one skit, he played himself as a guest at a Star Trek convention, where the audience focuses on trivial information about the show and Shatner's personal life. The annoyed actor advises them to "get a life". "For crying out loud," Shatner continues, "it's just a TV show!" He asks one Trekkie whether he has "ever kissed a girl". The embarrassed fans ask if, instead of the TV shows, they should focus on the Star Trek films instead. The angry Shatner leaves but because of his contract must return, and tells the Trekkies that they saw a "recreation of the evil Captain Kirk from episode 27, 'The Enemy Within.'"[37][26][38]

Although many Star Trek fans found the sketch to be insulting[2]: 77 it accurately portrayed Shatner's feelings about Trekkies, which the actor had previously discussed in interviews.[37] He had met overenthusiastic fans as early as March 1968, when a group attempted to rip Shatner's clothes off as the actor left 30 Rockefeller Plaza.[39] He was slower than others to begin attending conventions,[17] and stopped attending for more than a decade during the 1970s and 1980s.[35] In what Shatner described as one of "so many instances over the years" of fan excess, police captured a man with a gun at a German event before he could find the actor.[40]

The Saturday Night Live segment mentioned many such common stereotypes about Trekkies, including their willingness to buy any Star Trek-related merchandise, obsessive study of trivial details of the show, and inability to have conventional social interactions with others or distinguish between fantasy and reality.[37] Brent Spiner found that some could not accept that the actor who played Data was human,[26] Nimoy warned a journalist to perform the Vulcan salute correctly because "'Star Trek' fans can be scary. If you don't get this right you're going to hear about it",[41] and Roddenberry stated[42]

I have to limit myself to one [convention] in the East and one in the West each year. I'm not a performer and frankly those conventions scare the hell out of me. It is scary to be surrounded by a thousand people asking questions as if the events in the series actually happened.

A Newsweek cover article in December 1986 also cited many such stereotypes, depicting Star Trek fans as overweight and socially maladjusted "kooks" and "crazies".[37] The sketch and articles are representative of many media depictions of Trekkies, with fascination with Star Trek a common metaphor for useless, "fetishistic" obsession with a topic;[36] fans thus often hide their devotion to avoid social stigma.[43] Such depictions have helped popularize a view of devoted fans, not just of Star Trek, as potential fanatics. Reinforced by the well-known acts of violence by John Hinckley Jr. and Mark David Chapman, the sinister, obsessed "fan in the attic" has become a stock character in works such as the films The Fan (1981) and Misery (1990),[37] and the television series Black Mirror.[44]

Defenders

[edit]

Patrick Stewart objected when an interviewer described Trekkies as "weird", calling it a "silly thing to say". He added, "How many do you know personally? You couldn't be more wrong."[45] (According to Stewart, however, the actors dislike being called Trekkies and are careful to distinguish between themselves and the Trekkie audience.[46])

Isaac Asimov said of them, "Trekkies are intelligent, interested, involved people with whom it is a pleasure to be, in any numbers. Why else would they have been involved in Star Trek, an intelligent, interested, and involved show?"[47]

In 1998, the fan studies scholar Henry Jenkins published the journal article "Star Trek Rerun, Reread, Rewritten," in which he defended the behavior of Star Trek fans from an academic angle, arguing that they were "'poachers' of textual meanings who appropriate popular texts and reread them in a fashion that serves different interests."[48] Jenkins' subsequent monograph Textual Poachers (1992), which was written "to participate in the process of redefining the public identity of fandom", also focused at least in part on Star Trek fans.[49]

Religion

[edit]The central trio of Kirk, Spock and McCoy was modeled on classical mythological storytelling.[50] Shatner said:[51]

There is a mythological component [to pop culture], especially with science fiction. It's people looking for answers – and science fiction offers to explain the inexplicable, the same as religion tends to do. Although 99 percent of the people that come to these conventions don’t realize it, they’re going through the rituals that religion and mythology provide.

7,200 of the Elect are there to bear witness, and those 79 episodes are their revealed texts, the scarred tablets by which their lives here and now and beyond are charted.

According to Michael Jindra of the University of Wisconsin-Madison, the show's fandom "has strong affinities with a religious-type movement", with "an origin myth, a set of beliefs, an organization, and some of the most active and creative members to be found anywhere". While he distinguishes between Star Trek fandom and the traditional definition of religion that requires belief in divinity or the supernatural, Jindra compares Star Trek fandom to both "'quasi-religions,' such as Alcoholics Anonymous and New Age groups"—albeit more universal in its appeal and more organized—and civil religion.[52]

As with other faiths, Trekkies find comfort in their worship. Star Trek costume designer William Ware Theiss stated at a convention:[19]

The show is important psychologically and sociologically to a lot of people. For the unusual people at this convention, it's a big part of their lives, a help to them. I'm glad there are people who need something important in their lives and I'm glad they've found it in our shows. I don't want to elaborate on that; there are just some special people here who need the show in a special way.

The religious devotion of Star Trek's fans began almost immediately after the show's debut. When Roddenberry previewed the new show at a 1966 science-fiction convention, he and his creation received a rapturous response:[52]

After the film was over we were unable to leave our seats. We just nodded at each other and smiled, and began to whisper. We came close to lifting [Roddenberry] upon our shoulders and carrying him out of the room...[H]e smiled, and we returned the smile before we converged on him.

The showing divided the convention into two factions, the "enlightened" who had seen the preview and the "unenlightened" who had not.[52] However, the humanist Roddenberry disliked his role as involuntary prophet of a religion. Although he depended on Trekkies to support future Star Trek projects, Roddenberry stated that[42]

It frightens me when I learn of 10,000 people treating a Star Trek script as if it were Scripture. I certainly didn't write Scripture, and my feeling is that those who did were not treated very well in the end ... I'm just afraid that if it goes too far and it appears that I have created a philosophy to answer all human ills that someone will stand up and cry, 'Fraud!' And with good reason.

I'm not a guru and I don't want to be.

That there are no cries of "Amen, Brother," is simply a matter of style.

Religious aspects of Star Trek fandom nonetheless grew, according to Jindra, with the show's popularity. Conventions are an opportunity for fans to visit "another world...very much cut off from the real world...You can easily forget your own troubles as well as those of the world", with one convention holding an event in which a newborn baby was "baptized" into the "Temple of Trek" amid chanting. Star Trek museum exhibits, film studios, attractions, and other locations such as Vulcan, Alberta offer opportunities to perform pilgrimages to "our Mecca".[52] A fan astounded Nimoy by asking him to lay his hands on a friend's eyes to heal them.[53] Ethan Peck, a later Spock portrayer, said "When I'm meeting fans, sometimes they're coming to be confirmed, like I'm a priest".[54]

Fandom does not necessarily take the place of preexisting faith, with Christian and New Age adherents both finding support for their worldviews.[43]

Star Trek writer and director Nicholas Meyer compared the show to the Catholic Mass:[55]

Like the mass, there are certain elements of Star Trek that are immutable, unchangeable. The mass has its Kyrie, its Sanctus, Agnus Dei, Dies Irae, and so on... Star Trek has its Kirk, Spock, McCoy, Klingons, Romulans, etc., and the rest of the universe Roddenberry bequeathed us. The words of the mass are carved in stone, as are fundamental elements—the Enterprise, Spock, the transporter beam, and so forth—in Star Trek.

Meyer has also said:[52]

The words of the Mass remain constant, but heaven knows, the music keeps changing... Its humanism remains a buoyant constant. Religion without theology. The program's karma routinely runs over its dogma.

Anthropology

[edit]Intolerance in the 23rd century? Improbable! If man survives that long, he will have learned to take a delight in the essential differences between men and between cultures

We're following a philosophy of living. We are creating a society that [Roddenberry] dreamed of.

From before Star Trek's television début, Roddenberry saw the show as a way of depicting his utopian, idealized vision of the future. According to Andrew V. Kozinets of Northwestern University, many Trekkies identify with Roddenberry's idealism, and use their desire to bring such a future into reality as justification for their participation in and consumption of Star Trek media, activities, and merchandise, often citing the Vulcan philosophy of Infinite Diversity in Infinite Combinations. Such fans view Star Trek as a way to be with "'my kind of people'" in "'a better world'" where they will not be scorned or mocked despite being part of "stigmatized social categories".[43] Shatner agreed: "If we accept the premise that [the Star Trek story] has a mythological element, then all the stuff about going out into space and meeting new life – trying to explain it and put a human element to it – it’s a hopeful vision. All these things offer hope and imaginative solutions for the future."[51] Richard Lutz wrote:[56]

The enduring popularity of Star Trek is due to the underlying mythology which binds fans together by virtue of their shared love of stories involving exploration, discovery, adventure and friendship that promote an egalitarian and peace loving society where technology and diversity are valued rather than feared and citizens work together for the greater good. Thus Star Trek offers a hopeful vision of the future and a template for our lives and our society that we can aspire to.

Rather than "sit[ting] here and wait for the future to happen", local fan groups may serve as service clubs that volunteer at blood drives and food banks. For them,[43]

Star Trek provided positive role models, exploration of moral issues, scientific and technological knowledge and ideas, Western literary references, interest in television and motion picture production, intellectual stimulation and competition through games and trivia challenges, fan writing and art and music, explorations of erotic desire, community and feelings of communitas, and much more.

Despite their common interests fans differ in their levels of—and willingness to display and discuss—their devotion because of the perceived social stigma, and "[o]vercoming the Trekkie stigma entails a form of freedom and self-acceptance that has been compared to homosexual uncloseting." To outsiders the wearing of Starfleet uniforms, usually devalued as "costumes", is a symbol of their preconceptions of and unease with Trekkies. Kozinets cited the example of a debate at a Star Trek fan club's board meeting on whether board members should be required to wear uniforms to public events as an example of "not only...the cultural tensions of acceptance and denial of stigmatized identity, but the articulation and intensification of group meanings that can serve to counterargue stigma". The "vast majority of the club's time was spent discussing previous and upcoming television and movie products, related books, merchandise, and conventions", and club meetings and conventions focused on consumption rather than discussion of current affairs or societal improvement. (Perhaps appropriately, "Infinite Diversity in Infinite Combinations" originated in a third-season episode, "Is There in Truth No Beauty?", in which Roddenberry inserted a speech by Kirk praising the philosophy and associated medal. The "pointless" speech was, according to Shatner, a "thinly-veiled commercial" for replicas of the medal, which Roddenberry's company Lincoln Enterprises soon sold to fans.)[43]

There is a persistent stereotype that among Trekkies there are many speakers of the constructed Klingon language. The reality is less clear-cut, as some of its most fluent speakers are more language aficionados than people obsessed with Star Trek. Most Trekkies have no more than a basic vocabulary of Klingon, perhaps consisting of a few common words heard innumerable times over the series, while not having much knowledge of Klingon's syntax or precise phonetics.[57]

However, some fans have found that learning the languages of Klingon helps their abilities to enjoy the escapist immersion qualities of the show. They may try to get into character by cos-playing and acting as a member of an alien society by learning the language. The English classical work 'Hamlet' written by William Shakespeare and translated into Klingon has been added to the Folger Shakespeare Library.[58] There are courses and apps to help teach the Klingon language.

Demographics

[edit]

As of 2024[update], according to Akiva Goldsman, in a comparison of Star Trek and Star Wars, the latter's fan base is larger; the Marvel Cinematic Universe's fan base is larger than either. Although more Star Trek content is available on television than ever, Frakes said that of the fans he meets at conventions "very, very, very few" came to the franchise from new shows; "'Star Trek' fans, as we know, are very, very, very loyal — and not very young".[54] Despite fans' stated vision of Star Trek' as a way of celebrating diversity, Kozinets found that among the Trekkies he observed at clubs "most of the members were very similar in age, ethnic origin, and race. Out of about 30 people present at meetings, I noted only two visible minorities".[43]

While many stereotype Star Trek fandom as being mostly young males[2]: 77 and more men than women watch Star Trek TV shows,[26] female fans have been important members since the franchise's beginning. The majority of attendees at early conventions were women over the age of 21, which attracted more men to later ones.[52][2]: 77 [9] The two most important early members of fandom were women. Bjo Trimble was among the leaders of the successful effort to persuade NBC to renew the show for a third season, and wrote the first edition of the important early work Star Trek Concordance in 1969.[8]: 91, 280–281 Joan Winston and others on the female-dominated committee organized the initial 1972 New York convention and several later ones;[14] Winston was also one of the three female authors of "Star Trek" Lives![1]

While men participate in many fandom activities such as writing articles for fan publications and organizing conventions, women historically comprised the large majority of fan club administrators, fanfiction authors, and fanzine editors, and the Mary Sue-like "story premise of a female protagonist aboard the Enterprise who romances one of the Star Trek regulars, [became] very common in fanzine stories".[43][1][2]: 4, 57 So many single female fanzine editors left fan activities after getting married that one female fanzine editor speculated that the show was a substitute for sex.[2]: 9, 33 One scholar speculates that Kirk/Spock slash fiction is a way for women to "openly discuss sexuality in a non-judgmental manner".[59]: 323

Trekkie vs. Trekker

[edit]Star Trek fans disagree on whether to use the term Trekkie or Trekker.[2] The Oxford English Dictionary dates 'Trekker'—"A (devoted or enthusiastic) fan" of Star Trek— to 1967, stating that it is "sometimes used in preference to trekkie to denote a more serious or committed fan".[60] 'Trekkie' is thus, according to a 1978 journal article, "not an acceptable term to serious fans".[61] The distinction existed as early as May 1970, when the editor of fanzine Deck 6 wrote:

... when I start acting like a bubble-headed trekkie (rather than a sober, dignified — albeit enthusiastic — trekker).[2]: 4 [62]

By 1976, media reports on Star Trek conventions acknowledged the two types of fans:[63]

One Trekkie came by and felt compelled to explain, while paying for his Mr. Spock computer image, that he was actually a Trekker (a rational fan). Whereas, he said, a Trekkie worships anything connected with Star Trek and would sell his or her mother for a pair of Spock ears.[31]

In the TV special Star Trek: 25th Anniversary Special (1991), Leonard Nimoy attempted to settle the issue by stating that "Trekker" is the preferred term. During an appearance on Saturday Night Live to promote the 2009 Star Trek film, Nimoy – seeking to assure Chris Pine and Zachary Quinto, the "new" Kirk and Spock, that most fans would embrace them – initially referred to "Trekkies" before correcting himself and saying "Trekkers," emphasizing the second syllable, with a deadpan delivery throughout that left ambiguous whether this ostensible misstep and correction were indeed accidental or instead intentional and for comic effect.[64] In the documentary Trekkies, Kate Mulgrew stated that Trekkers are the ones "walking with us" while the Trekkies are the ones content to simply sit and watch Star Trek.

The issue is also shown in the film Trekkies 2, in which a Star Trek fan recounts a supposed incident during a Star Trek convention where Gene Roddenberry used the term "trekkies" to describe fans of the show, only to be corrected by a fan that stood up and yelled "Trekkers!" Gene Roddenberry responded with "No, it's 'Trekkies.' I should know – I invented the thing."

Other names

[edit]Star Trek fans who hold Star Trek: Deep Space Nine to be the best series of the franchise adopted the title of "Niner" following the episode "Take Me Out to the Holosuite", in which Captain Benjamin Sisko formed a baseball team called "The Niners".[citation needed]

Activities

[edit]Artistic multi media expressions of Trek fandom

[edit]There is a phenomenon of defacing the Canadian five-dollar notes that depict 19th century Canadian Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier, as Laurier's facial features on the CA$5 notes resemble Spock. In 2015, this was done as a tribute to Leonard Nimoy after his death. This was referred to as "Spocking fives".[65]

Star Trek has inspired commercially produced works of literature such as volumes of novels. However, fans have also produced numerous fan fiction productions and literature that seek to explore and continue hypothetical adventures of canonized characters. Seth MacFarlane, creator of The Orville, filmed a fan production as a teenager.[66] Star Trek alumni thespians have occasionally starred in these fan productions, such as Star Trek Continues. The erotic 'slash fiction' genre of fan fiction (Literotica) was rooted in the homoerotic pairings of Kirk and Spock in Star Trek fanzines of the 1970s written by female fans.[67]

Fan clubs and conventions

[edit]As with any immersive subculture fandom, for example, historical reenactors, or supporters of spectator sports, there are formalized bodies within the Trekkie subculture to facilitate immersion into the creation of Gene Roddenberry often by hosting conventions.

A Mecca of the Star Trek fandom is the Albertan township of Vulcan, Alberta. The town has embraced Star Trek themes as part of its community identity. An annual convention is held entitled Vul-con.[68]

There are many Star Trek fan clubs, among the largest being STARFLEET International and the International Federation of Trekkers. Some Trekkies regularly attend Star Trek conventions (called "cons"). In 2003, STARFLEET International was the world's largest Star Trek fan club;[69] as of January 1, 2020, it claimed to have 5,500+ members in 240+ chapters around the world.[70]

STARFLEET International

[edit]Within STARFLEET International (SFI), the local chapters are represented as 'ship' crews.

Eighteen people have served as president of the association since 1974. Upon election, the president is promoted to the fictional rank of Fleet Admiral and is referred to as the "Commander, Starfleet". Since 2004, the president has served a term of three years. Wayne Killough became the association's president on January 1, 2014. April 17, 2016 marked the first time a Commander, Starfleet died while in office. The late Wayne Killough was succeeded by Robin Woodell-Vitasek. As of January 1, 2020, Steven Parmley assumed office as the President of the association.

Since 1990, STARFLEET awards scholarships to post-secondary students who have been a member for a year of up to $1,000 to accomplish Roddenberry's Utopian futurist vision. Applicants must also be involved in organization, as they are required to submit a two-page essay of their involvement. The scholarships are named after the portrayers of characters such as: The James Doohan/Montgomery Scott Engineering & Technology Scholarship, DeForest Kelley/Doctor Leonard McCoy Memorial Medical & Veterinarian Scholarship, Gene Roddenbery Memorial/Sir Patrick Stewart Scholarship for Aspiring Writers and Artists, Space Explorer's Memorial Scholarship, Armin Shimerman/George Takei/LeVar Burton Scholarship for Business, Language Studies, and Education. The funds are contributed by fund-raising crew members.[71]

Whitewater jury

[edit]During the 1996 Whitewater controversy, a bookbindery employee named Barbara Adams served as an alternate juror. During the trial, Adams wore a Star Trek: The Next Generation-style Starfleet Command Section uniform, including a combadge, a phaser, and a tricorder.[72]

Adams was dismissed from the jury for conducting a sidewalk interview with the television program American Journal.[72] The major news media[who?] incorrectly reported that she was dismissed for wearing her Starfleet uniform to the trial. However, Adams noted that she had been dismissed because she had spoken to a reporter of American Journal about her Starfleet uniform but not about the trial.[73] Even though nothing she had said was deemed a trial-enclosure violation, the rule had been clearly stated that no juror was to communicate with the press in any manner whatsoever.

Adams stated that the judge at the trial was supportive of her. She said she believed in the principles expressed in Star Trek and found it an alternative to "mindless television" because it promoted tolerance, peace, and faith in mankind.[72] Adams subsequently appeared in the documentaries Trekkies and Trekkies 2.

In popular culture

[edit]This article needs additional citations for verification. (March 2017) |

I had originally not wanted to see Galaxy Quest because I heard that it was making fun of Star Trek and then Jonathan Frakes rang me up and said 'You must not miss this movie! See it on a Saturday night in a full theatre.' And I did and of course I found it was brilliant. Brilliant. No one laughed louder or longer in the cinema than I did

Trekkies have been parodied in several films, notably the science fiction comedy Galaxy Quest (1999). Actors such as Stewart and Jonathan Frakes have praised the accuracy[74][75] of its satiric portrayal of a long-canceled science-fiction television series, its cast members, and devoted fans known as "Questerians".[76][77] The main character Jason Nesmith, representing Shatner, repeats the actor's 1986 "Get a life!" statement when an avid fan asks him about the operation of the fictional vessel.

Star Trek itself has satirized Trekkies' excessive obsession with imaginary characters, through Reginald Barclay and his holodeck addiction.[78][26]

One episode of Futurama called "Where No Fan Has Gone Before" was dedicated to parodying Trekkies. It included a history whereby Star Trek's fandom had grown into a religion. Eventually, the Church of Star Trek had grown so strong that it needed to be abolished from the Galaxy and even the words "Star Trek" were outlawed.

The romantic comedy Free Enterprise (1999) chronicled the lives of two men who grew up worshipping Star Trek and emulating Captain Kirk. Most of the movie centers on William Shatner, playing a parody of himself, and how the characters wrestle with their relationships to Star Trek.

A Trekkie featured in one episode of the television series The West Wing, during which Josh Lyman confronts the temporary employee over her display of a Star Trek pin in the White House.

The comedy film Fanboys (2009) makes frequent references to Star Trek and the rivalry between Trekkies and Star Wars fans. William Shatner makes a cameo appearance in the film.

The comedy-drama film Please Stand By (2017) chronicles Wendy Welcott, a brilliant young woman with autism and a fixation on Star Trek. She runs away from her group home in an attempt to submit her 450-page script to a Star Trek writing competition at Paramount Pictures.

The Family Guy episode "Not All Dogs Go to Heaven" features a Star Trek convention and many Trekkies. One Trekkie comes to the convention with the mumps, and upon Peter Griffin seeing him, he impulsively pushes his daughter Meg into the Trekkie and forces her to take her picture with him (believing him to be in costume as an alien from Star Trek). Since Meg was not immunized, she catches the mumps from the Trekkie and ends up bedridden.

On the CBS-TV sitcom The Big Bang Theory, the four main male characters are shown to be Trekkies, playing the game of "Klingon Boggle" and resolving disputes using the game of "rock-paper-scissors-lizard-Spock". Wil Wheaton of Star Trek: The Next Generation fame has made multiple guest appearances playing an evil version of himself. LeVar Burton, Brent Spiner, Leonard Nimoy (as a voice actor),[79] William Shatner and George Takei have also appeared on the series.

The films Trekkies (1997) and its sequel Trekkies 2 (2004) chronicled the life of many Trekkies.

Famous fans

[edit]During my time we had two chairmen of the joint chiefs of staff, at different times of course, on the bridge, both of whom asked my permission to sit on the captain's chair.

Actors and comedians

[edit]

- Kawa Ada - Afghan-Canadian actor, writer and producer, watched Star Trek: The Next Generation and used to collect unopened Star Trek figurines.[80]

- Freema Agyeman - Actress (played Martha Jones in Doctor Who), watched Star Trek: The Next Generation and Star Trek: Deep Space Nine and at least once attended a convention.[81]

- Jason Alexander - Actor and comedian, wanted to guest star on a Star Trek episode, ended up being on Star Trek: Voyager.[82]

- Bill Bailey - British comedian, named his child after the Deep Space Nine character Dax. "I may just have given him too much baggage," Bailey has joked. "I'll tell him he's named after the German stock exchange."[83]

- John Barrowman - Actor (played Captain Jack Harkness in Doctor Who and its spin-off Torchwood), is a huge fan of Star Trek: Deep Space Nine.[84]

- Candice Bergen - Actress, attended at least one convention in 1976.[31]

- Nicolas Cage - Actor, when asked in January 2023 if he would be willing to join the Star Wars universe, he responded: “No is the answer, and I’m not really down... I’m a Trekkie man. I’m on the Enterprise. That’s where I roll.”[85]

- Robert Carlyle - Actor (played Dr. Nicholas Rush on Stargate Universe), has admitted to being a huge fan of Star Trek: The Original Series as a child.[86]

- Jim Carrey - Actor and comedian. Regularly impersonated William Shatner on In Living Color.

- Jeremy Clarkson - Television personality. Stated in 2013 during Series 20, episode 3 of Top Gear that he was a huge fan of the franchise during an interview with Benedict Cumberbatch.

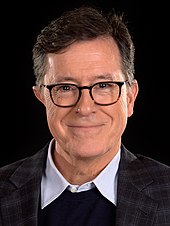

- Stephen Colbert - Actor, comedian and television host, interviewed George Takei on The Late Show with Stephen Colbert in 2016 and told him that he had been a Star Trek fan since he was "knee-high to a grasshopper" and that it was "one of the greatest shows ever on television".[87]

- Rosario Dawson - Actress, claimed that Star Trek is "one of [her] favorite things in the world". When Conan was on NBC, the actress revealed she and her brother have argued in Klingon. She also held an online petition to appear in Star Trek Into Darkness.[88][89]

- Jim Davidson - British comedian.[90]

- Megan Fox - Actress[91]

- Whoopi Goldberg - Actress and comedian, she specifically requested a role in Star Trek: The Next Generation because the character Nyota Uhura inspired her early acting career. She played the recurring role of an alien named Guinan on the television series and in the film Star Trek Generations.[92] She also had an uncredited appearance in Star Trek: Nemesis during the wedding scene towards the movie's beginning.

- Kelsey Grammer - Actor, is a huge fan of Star Trek.[citation needed] He guest-starred on the Next Generation episode "Cause and Effect" and had Patrick Stewart and Brent Spiner each guest star in two episodes of his sitcom Frasier. Furthermore, he speaks Klingon in the Frasier episode "Star Mitzvah".

- Tom Hanks - Actor, and a huge fan since childhood. He is purported to know the title of every Next Generation episode.[75] He was considered for the role of Zefram Cochrane in Star Trek: First Contact, but had to turn it down due to a scheduling conflict.[93]

- Susannah Harker - Actress, played Jane Bennet in Pride and Prejudice (1995).

- Angelina Jolie - Actress, confesses to having a childhood crush on Mr. Spock.[88]

- Gabriel Köerner - A profilee in Trekkies who went on to guest star on The Drew Carey Show and as the "Star Trek Geek" on the game show Beat the Geeks.

- Mila Kunis - Actress, told GQ in 2011 she has vintage Star Trek figures and a signed photo from Leonard Nimoy. She's even attended a Trek conference. "I went to the Star Trek Experience in Vegas maybe five years ago. I hung out with a bunch of fake characters inside Quark's bar. There were all these actors there pretending to be the different characters from the different shows. Yes, I loved it." Her favorite series is The Next Generation.[89]

- Virginia Madsen - Actress, is a huge fan of the original series, and in an interview, admitted that she was sobbing so hard when Spock died in Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan, she had to go home right away.[citation needed] She also guest starred in the Star Trek: Voyager episode "Unforgettable".[94]

- Bill Maher - Comedian, remarked in an interview with George Takei that he had seen every Star Trek episode.

- James Marsters - Actor, played Spike on Buffy the Vampire Slayer. Auditioned to play Shinzon in Star Trek Nemesis.[95]

- Eddie Murphy - Actor and comedian, he nearly starred in Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home and when his million-dollar contract with Paramount Pictures arrived to be signed, Murphy delayed signing it for nearly an hour because he was so engrossed with an episode of the original series.[96]

- Christopher Plummer - Actor, was a contemporary of William Shatner in Canadian theatre and enjoyed watching the series. Played General Chang in Star Trek VI: The Undiscovered Country.

- Freddie Prinze Jr. - Actor, stated he grew up watching Star Trek.[97]

- Dan Schneider - TV actor, writer and producer, known for being the creator of Nickelodeon TV series like All That, The Amanda Show, Drake & Josh, Zoey 101, iCarly and more. In an interview with Fanlala, he spoke to releasing iCarly on the same date as the original Star Trek premiere, saying that he is "a huge fan of the original Star Trek." He also said that he learned a lot from Gene Roddenberry and that the show meant a lot to him as a child.[98][99][100]

- Mira Sorvino - Academy Award-winning actress, stated in an interview with Conan O'Brien that she was a huge fan of the original series. Her father, Paul Sorvino, appeared as Nikolai Rozhenko, in the Next Generation episode "Homeward" the human brother and biological child of Worf's human foster parents.[91]

- Ben Stiller - Actor and comedian, has been a huge fan of Star Trek since he was a kid. Stiller's production company, "Red Hour Films", is named after an alien population's "specified riot time" featured in the original series episode "The Return of the Archons". A clip of the original series episode "Arena" was shown in his film Tropic Thunder (2008).[101] In the film Zoolander (2001), Stiller named the villain "Mugatu", after a similarly named simian creature in the original series episode "A Private Little War".[102] Stiller's film The Cable Guy (1996) features a scene where Chip and Steven duel at Medieval times, Chip chants the battle music from the episode "Amok Time" and quotes several lines from the same episode.[103]

- William Tarmey - Actor, played Jack Duckworth on Coronation Street. He changed his character's final line before his death to match Captain Kirk's at the end of Star Trek Generations[104]

- Karl Urban - Actor, has been a huge fan of the series since he was seven years old and was cast in the role of Leonard McCoy in the 2009 Star Trek film. He actively pursued the role after rediscovering the series on DVD with his son.[105] In his Blu-ray commentary, director J. J. Abrams stated that a line in the film explaining the origin of the character's nickname, "Bones", had not been scripted and instead was thought up by Urban while filming the scene.[106]

- Olivia Wilde - Actress, Wilde told i09 she's been a huge fan since she was very young. "I grew up as a Trekkie, which is really funny," said Wilde. "I think Star Trek, they were always great female roles, but there's no reason the captain shouldn't be a woman."[89]

- Robin Williams - Actor and comedian, according to Walter Koenig's book Chekov's Enterprise, Williams visited the set during filming of Star Trek: The Motion Picture and admitted he was a huge fan of the series. He was originally considered for the role of a time traveling con-man in the Next Generation episode "A Matter of Time" but was unable to star due to a scheduling conflict with Hook (1991). Williams made reference to Seven of Nine in his "Weapons of Self-Destruction" comedy special.

- Some of the principal actors in second-generation Star Trek productions were fans of the franchise at the time of their selection, including Michael Dorn, Jolene Blalock,[citation needed] Wil Wheaton and (according to Wheaton), LeVar Burton.[107]

Hollywood movie and television directors and producers

[edit]

- Mel Brooks - Film director, screenwriter, comedian, actor, producer, composer and songwriter, is a huge fan of the series (according to Brent Spiner in the documentary Trekkies).

- David A. Goodman - Family Guy executive producer, is a major fan of Star Trek.[citation needed] He has written an episode of Futurama entirely devoted to Star Trek, and later four episodes of Star Trek: Enterprise. He even paid tribute to the 20th anniversary of Star Trek: The Next Generation by spoofing the cliffhanger ending of "The Best of Both Worlds, Part I" and using it as the cliffhanger ending of the 100th episode of Family Guy, "Stewie Kills Lois".

- Justin Lin - Director of some of the Fast and Furious movies is a huge fan of the franchise and was chosen by J. J. Abrams to direct and co-produce Star Trek Beyond because of that.

- George Lucas - The Star Wars creator amazed Clint Howard by, during an audition, immediately citing his role years earlier as Balok from "The Corbomite Maneuver". Howard said that he wanted to yell "Get a life" at the filmmaker.[108][109][110]

- Seth MacFarlane - The creator of Family Guy, American Dad! and The Cleveland Show is an avid fan.[citation needed] He has embedded dozens of Star Trek references in his shows, and twice guest starred on Enterprise. He says his favorite Star Trek series is The Next Generation and he reunited the cast of that show for the Family Guy episode "Not All Dogs Go to Heaven". His sci-fi comedy-drama series The Orville was inspired by Star Trek.

- Trey Parker and Matt Stone - Creators of South Park are Star Trek fans[citation needed] and have put many references to the franchise in their show.

Musicians

[edit]

- Welsh rock group Lostprophets members are huge fans of the series.[111]

- Mick Fleetwood - British musician, appeared in an episode of The Next Generation.

- Eat Static - English DJ whose name Eat Static comes from the film Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan.

- Mike Oldfield - Musician.[112]

- Roy Orbison - The singer-songwriter was a huge fan of Star Trek and would often play the original series theme at the beginning of his shows.[113] In Star Trek: First Contact, his recording of "Ooby Dooby" is the first piece of human culture ever shared with an (acknowledged) alien race.

- Elvis Presley - Singer and actor.[114]

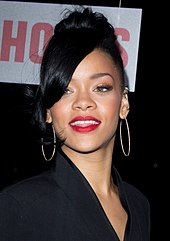

- Rihanna - The singer has been a huge fan of Star Trek since she was a child and was introduced to the series by her father. She also recorded the song "Sledgehammer" for the reboot film Star Trek Beyond.[115]

- Frank Sinatra - Singer and actor, "never missed" The Next Generation.[75]

- Carrie Underwood - Country singer, is a huge fan of Star Trek: The Next Generation, and admits to having a crush on Patrick Stewart.[116]

- D'arcy Wretzky - Former bassist of The Smashing Pumpkins, said she was "a big 'Star Trek' fan, but I'm not into the conventions or the ears or anything like that".[117]

- Zakk Wylde - Former guitarist for Ozzy Osbourne and founder of Black Label Society.[118]

Politicians and world leaders

[edit]

- King Abdullah II of Jordan - As crown prince, he has a cameo appearance in an episode of Star Trek: Voyager.[119]

- Pete Buttigieg - Current United States Secretary of Transportation and former Mayor of South Bend, Indiana. Lifelong fan of Star Trek.[120]

- Hans Dijkstal - Dutch politician, Minister of the Interior and Deputy Prime Minister.[121]

- Al Gore - Forty-fifth Vice President of the United States from 1993 to 2001. He watched the series more than he studied, according to his Harvard University roommate Tommy Lee Jones.[122]

- Alan Keyes - American conservative (known best for his career runs for president) has stated his favorite television program is Star Trek: Deep Space Nine. He once said about Star Trek, "There's something basically clean and decent and all-American about the respect for human dignity that Star Trek creator Gene Roddenberry showed."[123]

- Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. - reportedly described himself to Nichelle Nichols as "the biggest Trekkie on the planet", for the message (controversial at the time) that it sent about white people and black people working together as equals and urged Nichols to remain on the show, which she had planned to leave.[124]

- Jack Layton and Olivia Chow - The married couple, Layton leader of the New Democratic Party of Canada and Chow a Mayor of Toronto, were "devoted Trekkies" and had tailor-made Starfleet uniforms.[125]

- John Horgan - New Democratic Party Premier of British Columbia[126]

- Lewis "Scooter" Libby - His Yale classmate Donald Hindle said Libby had the "decidedly nonpolitical talent" of remembering all 79 Star Trek episodes and "knew all the titles, too".[127]

- Barack Obama - [128] Leonard Nimoy hinted that Obama greeted him with the Vulcan salute.[129] Obama further requested a screening of the new Star Trek film at the White House.[130]

- Dan Maffei - Congressman, (Democratic Party-NY-25) participated in Stephen Colbert's "Better Know a District" segment on The Colbert Report. In the interview, Maffei and Colbert donned goatees in reference to Spock in the original series episode "Mirror, Mirror". At the end of the interview, Maffei and Colbert exchanged the Vulcan salute.[131]

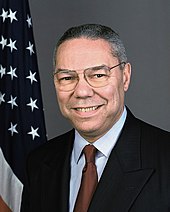

- Colin Powell - United States Secretary of State from 2001–2005, visited the set of The Next Generation.[132]

- Carlos Alvarado Quesada - President of Costa Rica.[133]

- Ronald Reagan - Former President, visited the set of The Next Generation in 1991 during filming of "Redemption". He remarked "I like them [the Klingons]. They remind me of Congress."[134]

- Alex Salmond - Scotland's former First Minister, with his favourite being The Original Series and Star Trek: Voyager.[135]

- Leo Varadkar - The former Taoiseach of Ireland was a huge fan of Star Trek growing up.[136]

- David Wu - Oregon Congressional Representative, delivered a heavily Trek-infused speech to the House of Representatives on January 10, 2007.[137]

- Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez - New York Congressional Representative, recalled watching Voyager as a young child.[138]

Science fiction writers

[edit]- Isaac Asimov - A close personal friend of Gene Roddenberry. He attended the first public screening of "Where No Man Has Gone Before" and attended numerous conventions during the 1970s.[139]

- Malorie Blackman - Author and former UK Children's Laureate. The blurb to the UK edition of her novel Noughts and Crosses says that she is a huge fan of Star Trek and her dream job would be to captain the USS Enterprise.

- Bjo Trimble - who helped spearhead the letter writing campaign that convinced NBC to continue Star Trek for a third season.

Scientists, engineers, inventors and entrepreneurs

[edit]

- Jeff Bezos - billionaire who made his fortune as a technology and retail entrepreneur. He is also an electrical engineer and computer scientist. He appeared in a cameo as an alien Starfleet official in the film Star Trek Beyond.[citation needed]

- Sir Richard Branson - The founder of the Virgin Group. He named the first spacecraft of his Virgin Galactic venture VSS Enterprise and the second one VSS Voyager.[140]

- Martin Cooper - Invented the first Mobile phone, was inspired to do so after seeing Captain Kirk use his communicator.[141]

- Stephen Hawking - Scientist, who played a holodeck version of himself on the Next Generation episode "Descent" (thus becoming the only person in a Star Trek episode or film credited as "Himself"[142]). While on the set he wanted to see the Enterprise's warp engine room set. After seeing it he commented, "I am working on that."

- Michael Jones - Chief technologist of Google Earth, has cited the tricorder's mapping capability as one inspiration in the development of Keyhole/Google Earth.[143]

- Elon Musk - A billionaire business magnate, investor, engineer and inventor. Famous for Tesla and SpaceX and was referenced in Star Trek: Discovery.[citation needed]

- Bill Emerson - President and Chief Operating Officer of Rocket Companies, Inc.

- Bill Nye - Scientist and television host of Bill Nye the Science Guy, praised Star Trek by stating that "In all the versions of Star Trek, the future for humankind is optimistic. They've solved all the problems of food, clothing and shelter. And you know how they solved them? Through science. Not only that, in the Star Trek future, everybody gets along..."[144]

- Randy Pausch - The late Carnegie Mellon University professor who wrote The Last Lecture. He appeared in a cameo in the 2009 Star Trek film.[citation needed]

- Steve Wozniak - A computer engineer and entrepreneur who credited watching Star Trek and attending Star Trek conventions while as a youth as his source of inspiration for co-founding Apple Inc. in 1976, which would later become the world's largest information technology company by revenue and the world's third-largest mobile phone manufacturer.[citation needed]

- Neil deGrasse Tyson - Astrophysicist, cosmologist, author, and science communicator. He mentioned in an episode of StarTalk Radio, while talking to Wil Wheaton, that he styles his sideburns in a point as an homage to Star Trek.[145]

Astronauts and NASA personnel

[edit]

"What was really great about Star Trek when I was growing up as a little girl is not only did they have Lt. Uhura played by Nichelle Nichols as a technical officer […] At the same time, they had this crew that was composed of people from all around the world and they were working together to learn more about the universe. So that helped to fuel my whole idea that I could be involved in space exploration as well as in the sciences."

"Now, Star Trek showed the future where there were black folk and white folk working together. I just looked at it as science fiction, 'cause that wasn't going to happen, really. But Ronald saw it as science possibility. He came up during a time when there was Neil Armstrong and all of those guys; so how was a colored boy from South Carolina - wearing glasses, never flew a plane - how was he gonna become an astronaut? But Ron was one who didn't accept societal norms as being his norm, you know? That was for other people. And he got to be aboard his own Starship Enterprise."

- Franklin Chang Díaz - Third NASA Latin American astronaut, first Latin American immigrant and first of Costa Rican descent into space.[133]

- Samantha Cristoforetti - First Italian astronaut considers herself to be a huge fan of Star Trek.[146] She famously drank the first espresso in space while wearing her Star Trek uniform.

- Michael Fincke - Astronaut. He was a guest star on the final episode of Star Trek: Enterprise along with fellow astronaut Terry W. Virts.[147] He was also featured in the Star Trek: First Contact Blu-ray special features, talking about working in space and Star Trek influences.

- Chris Hadfield - Whose Exchanges on public media (Facebook, Tumblr, YouTube and Google+) with William Shatner and other Star Trek actors are famous.[148]

- Mae Jemison - An American physician and NASA astronaut. She became the first African American woman to travel in space when she went into orbit aboard the Space Shuttle Endeavour on September 12, 1992. Appeared as Lt. Palmer in the Next Generation episode "Second Chances".

“I remember watching my first episode of ‘Star Trek’ at the age of 9, and seeing the beautiful depictions of the regions of the universe that they were exploring. I remember thinking ‘I want to do that. I want to find new and beautiful places in the universe'.”

- Ronald McNair - The second black person in space and one of the seven astronauts who died in the January 28, 1986 Challenger disaster. According to his brother, Star Trek had a positive impact on his brother.

- Swati Mohan[1] - An Indian-American aerospace engineer and was the Guidance and Controls Operations Lead on the NASA Mars 2020 mission.

- Terry W. Virts - Astronaut. He was a guest star on the final episode of Star Trek: Enterprise along with fellow astronaut Michael Fincke.[147] He was also featured in the Star Trek V: The Final Frontier Blu-ray special features, talking about NASA and Star Trek influences.

Others

[edit]- Tracey Emin - A British artist, who created a hand-sewn blanket entitled Star Trek Voyager which was auctioned for £800,000 in 2007.[149]

- Gustavo Gómez Córdoba - Colombian radio journalist. He is an anchor at Caracol Radio.

- Damon Hill - Formula One world champion of 1996. In his autobiography, he stated he watched the original series as a child.

- Hosts of the Cum Town podcast: Nick Mullen, Stavros Halkias and Adam Friedland - occasionally reference the show to mock its actors and celebrities who happen to look like them (notably Eric Trump and Odo).[150]

References and footnotes

[edit]- ^ a b c d e Coppa, Francesca (2006). "A Brief History of Media Fandom". In Helleksen, Karen; Busse, Kristina (eds.). Fan Fiction and Fan Communities in the Age of the Internet. McFarland. p. 41. ISBN 0-7864-2640-3.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Verba, Joan Marie (2003). Boldly Writing: A Trekker Fan & Zine History, 1967-1987 (PDF). Minnetonka MN: FTL Publications. ISBN 0-9653575-4-6. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-09-10.

- ^ Page, Don (1968-08-15). "'Star Trek' Lives Despite Taboos". Toledo Blade. Retrieved April 29, 2011.

- ^ Jones, Dorothy (September 1968). "The Elf in the Starship Enterprise". If. p. 48.

- ^ Nimoy, Leonard (1995). I Am Spock. Hyperion. pp. 79–80. ISBN 0786861827.

- ^ @TheRealNimoy (2011-02-11). "The only time I ever appeared in public as Spock. Medford, Oregon Pear Blossom Festival. 1967 ? LLAP http://twitpic.com/3yr7hk" (Tweet). Retrieved 2015-08-25 – via Twitter.

- ^ Harrison, Scott (2011-04-25). "'Star Trek' protest". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved April 26, 2011.

- ^ a b Reid, Robin Anne (2009). Women in Science Fiction and Fantasy: Overviews. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-0-313-33591-4.

- ^ a b c "Where Trekkies Were Born". Newsweek. 2009-05-06. Archived from the original on 2010-08-28. Retrieved May 2, 2011.

- ^ "They Wanted Star Trek". The Calgary Herald. Canadian Press. 1969-07-22. p. 8. Retrieved April 29, 2011.

- ^ a b Buck, Jerry (1972-03-15). "'Star Trek' still cruising space on TV". Eugene Register-Guard. Associated Press. pp. 13B. Retrieved March 4, 2011.

- ^ a b c Sedgeman, Judy (1972-05-29). "Fan of Star Trek Works At Getting TV Show Returned". St. Petersburg Times. Retrieved May 4, 2011.

- ^ a b Montgomery, Paul L. (1973-03-11). "'Star Trekkies' Show Devotion". The Ledger. Lakeland, Florida. The New York Times. p. 34. Retrieved May 12, 2011.

- ^ a b Grimes, William (September 21, 2008). "Joan Winston, 'Trek' Superfan, Dies at 77". The New York Times. pp. A34. Retrieved April 2, 2010.

- ^ StarTrek.com Staff (2012-01-20). "Celebrating 40 Years since Trek's 1st Convention". startrek.com. Retrieved January 12, 2013.

- ^ Nichols, Nichelle; Abramson, Stephen J. (interviewer) (2010-10-13). Nichelle Nichols. North Hollywood, California: Archive of American Television, The Television Academy Foundation.

- ^ a b "We're All Trekkies Now". Newsweek. 2009-04-25. Retrieved May 2, 2011.

- ^ Reitman, Valerie (2005-04-08). "'Star Trek' Bit Players Cling On". Los Angeles Times. p. 1. Retrieved May 14, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e Hale, Barrie (1975-04-26). "Believing in Captain Kirk". Calgary Herald. p. 10. Retrieved May 14, 2011.

- ^ a b "Star Trek Promoters Out To Make A Fast Buck". The Ledger. Lakeland, Florida. The New York Times Syndicate and News Service. 1976-02-22. pp. 9F. Retrieved May 2, 2011.

- ^ "The British Star Trek Convention (1974 & 1975 cons)". Fanlore.

- ^ a b "Another Final Frontier: 'Star Trek' at Space Museum". The New York Times. 1992-03-03. Retrieved May 24, 2011.

- ^ a b Meehan, Eileen R. (2005). Why TV is not our fault: television programming, viewers, and who's really in control. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 0-7425-2486-8.

- ^ a b "The Trekkie Fad..." Time. 1975-09-08. Archived from the original on 2007-03-03. Retrieved March 5, 2011.

- ^ Shult, Doug (1972-07-03). "Cult Fans, Reruns Give 'Star Trek' an Out of This World Popularity". Milwaukee Journal. Archived from the original on 2016-05-06. Retrieved March 4, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e Teitelbaum, Sheldon (1991-05-05). "How Gene Roddenberry and his Brain Trust Have Boldly Taken 'Star Trek' Where No TV Series Has Gone Before : Trekking to the Top". Los Angeles Times. p. 16. Archived from the original on 2015-11-06. Retrieved April 27, 2011.

- ^ Harmetz, Aljean (November 2, 1986). "New 'Star Trek' Plan Reflects Symbiosis of TV and Movies". The New York Times. p. 31. Retrieved 2015-02-11.

- ^ a b Poe, Stephen Edward (1998). A Vision of the Future. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 0-671-53481-5.

- ^ Millrod, Jack (1996-09-16). "The Trek Continues (? Illegible)". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. pp. D1. Retrieved April 26, 2011.

- ^ "Trekking To Blast-Off". Toledo Blade. Associated Press. 1975-08-21. p. 34. Retrieved May 2, 2011.

- ^ a b c Ahl, David H. (1977). The Best of Creative Computing, vol. 2. Morristown NJ: Creative Computing. p. 162. ISBN 0-916688-03-8.

- ^ Strauss, Mark (2014-07-10). "Declassified Memos Reveal Debate Over Naming the Shuttle "Enterprise"". io9. Retrieved 21 August 2015.

- ^ Cerone, Daniel (1994-04-02). "Trek On Into the 21st Century". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved March 7, 2011.

- ^ Damien, Walter (9 May 2012). "Fandom matters: writers must respect their followers or pay with their careers". Retrieved 9 May 2012.

- ^ a b Martin, Sue (1986-09-07). "Star Trek: Five-Year Mission Turns Into 20". San Francisco Chronicle. p. 49.

- ^ a b Tainer, Mike (2011-04-28). "N.F.L. Draft Boards Take on Lives of Their Own". The New York Times. pp. B12. Retrieved April 28, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e Jenkins, Henry (1992). Textual Poachers: Television Fans and Participatory Culture. London: Routledge. pp. 9–13. ISBN 978-1-135-96469-6.

- ^ Zoglin, Richard (Nov 28, 1994). "Trekking Onward". Time. Archived from the original on September 30, 2007.

- ^ Lowry, Cynthia (March 29, 1968). "TV Fans Save Space Ship Enterprise From Mothballs". Florence Times—Tri-Cities Daily. Florence, AL: Tri-Cities Newspapers, Inc. Associated Press. p. 15. Retrieved 2013-11-07.

- ^ Dominguez, Robert (1999-05-17). "William Shatner's Trek Never Ends The Actor-author Keeps Seeking New Challenges While Feeding Fans' Hunger For All Things Kirk". New York Daily News. Archived from the original on 2012-01-12. Retrieved October 14, 2011.

- ^ Boucher, Geoff (2009-05-11). "Leonard Nimoy: 'Star Trek' fans can be scary". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 1 March 2015.

- ^ a b c Bob Thomas (1976-05-25). "Roddenberry would like to leave 'Star Trek' behind". Williamson Daily News. Williamson, West Virginia. Associated Press. p. 14. Retrieved May 15, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Kozinets, Robert V. (June 2001). "Utopian Enterprise: Articulating the Meanings of Star Trek's Culture of Consumption". The Journal of Consumer Research. 28 (1): 67–88. doi:10.1086/321948. JSTOR 10.1086/321948.

- ^ Jordan Hoffman (2018-01-04). "Black Mirror's meditation on Star Trek: reinforcing Trekker stereotypes? | Television & radio". The Guardian. Retrieved 2018-01-19.

- ^ Gostin, Nicki (2008-03-29). "Mr. Stewart Loves His Trekkies". Newsweek. Retrieved May 2, 2011.

- ^ Brady, James (1992-04-05). "In Step With: Patrick Stewart". Parade. p. 21. Retrieved April 28, 2011.

- ^ Asimov, Isaac (August 1976). "The Conventions as Asimov Sees Them". Starlog. p. 43. Retrieved 17 October 2013.

- ^ Jenkins, Henry (1988). "Star Trek Rerun, Reread, Rewritten: Fan Writing as Textual Poaching". Critical Studies in Mass Communication. 5 (2): 85. doi:10.1080/15295038809366691.

- ^ Jenkins, Henry (1992). Textual Poachers: Television Fans and Participatory Culture. London: Routledge. p. 8. ISBN 978-1-135-96469-6.

- ^ Social History: Star Trek as a Cultural Phenomenon URL accesses May 31, 2013

- ^ a b McDonald, Glen (March 12, 2015). "William Shatner talks 'Star Trek,' sci-fi and fans". The News & Observer. Retrieved August 31, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f Jindra, Michael (1994). "Star Trek Fandom as a Religious Phenomenon". Sociology of Religion. 55 (1): 27–51. doi:10.2307/3712174. JSTOR 3712174.

- ^ Michaels, Marguerite (December 10, 1978). "A Visit to Star Trek's Movie Launch". Parade. pp. 4–7. Retrieved June 1, 2022.

- ^ a b Vary, Adam B. (2024-03-27). "The Future of 'Star Trek': From 'Starfleet Academy' to New Movies and Michelle Yeoh, How the 58-Year-Old Franchise Is Planning for the Next Generation of Fans". Variety. Retrieved 2024-03-31.

- ^ Meyer, Nicholas (2009). The View from the Bridge: Memories of Star Trek and a Life in Hollywood. Viking Penguin. ISBN 978-0-452-29653-4.

- ^ Lutz, Richard (August 2015). "Social Cohesiveness" (PDF). Human Rights Coalition (Australia). Retrieved August 31, 2015.

- ^ "There's No Klingon Word for 'Hello", Slate Magazine, May 7, 2009. Retrieved May 8, 2009

- ^ "Shakespeare, in the original Klingon". Shakespeare & Beyond. 2016-09-16. Retrieved 2023-02-10.

- ^ Bacon-Smith, Camille (1992). Enterprising Women. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 0-8122-1379-3.

- ^ trekker, n.. Oxford University Press.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Byrd, Patricia (Spring 1978). "Star Trek Lives: Trekker Slang". American Speech. 53 (1): 52–58. doi:10.2307/455340. JSTOR 455340.

- ^ "trekkie n." Science Fiction Citations. Retrieved March 4, 2011.

- ^ Dickson, Doris (August 9, 1976). "Loyal fans of Star Trek". The Windsor Star. p. 28. Retrieved March 4, 2011.

- ^ Chris Pine, Zachary Quinto, Leonard Nimoy, Seth Meyers. Update Feature: Star Trek. Hulu. Archived from the original on February 23, 2011.

- ^ Quito, Anne (2015-03-01). "Canadians "Spock" their banknotes to honor Leonard Nimoy". Quartz. Archived from the original on 2022-09-09. Retrieved 2022-09-09.

- ^ Lovette, J. (Dec 26, 2017). "Watch Teenage Seth MacFarlane Play Captain Kirk in a Fan Film". comicbook.com. Retrieved Dec 31, 2017.

- ^ Jenna Sinclair. "A SHORT HISTORY OF EARLY K/S or HOW THE FIRST SLASH FANDOM CAME TO BE". Beyond Dream Press. Archived from the original on July 7, 2011. Retrieved December 31, 2017.

- ^ Dormer, D. (Jul 8, 2016). "Vul-con set to celebrate 50 years of star trek". CBC news Calgary. Retrieved Dec 31, 2017.

- ^ Folkard, Claire (2003). Guinness World Records 2004. Bantam Books. p. 167. ISBN 978-0-553-58712-8.

- ^ STARFLEET Database, CompOps, Fleet Strength

- ^ Murray, Arthur (June 1, 2017). "Study Long and Prosper:Science Fiction Can Help Pay For College". US News. Retrieved Dec 31, 2017.

- ^ a b c "Judge beams 'trekkie' juror from Whitewater case". CNN. March 14, 1996. Archived from the original on December 18, 2003. Retrieved February 21, 2011.

- ^ Interview with Mike Jerrick on Sci-Fi Channel's information fandom news series Sci-Fi Buzz.

- ^ a b c "Patrick Stewart - Jean Luc Picard, Captain of the Enterprise". BBC. Archived from the original on 15 November 2001. Retrieved 13 November 2016.

- ^ a b c Appleyard, Bryan (2007-11-04). "Patrick Stewart: Keep on trekkin'". The Sunday Times. Archived from the original on 2008-05-11. Retrieved 2017-09-12.

- ^ Kempley, Rita (1999-12-25). "'Galaxy Quest': Set Phasers on Fun". Washington Post. Retrieved 2013-04-24.

- ^ Errigo, Angie. "Reviews: Galaxy Quest". Empire. Bauer Consumer Media. Retrieved May 4, 2011.

- ^ Joyrich, Lynne (Winter 1996). "Feminist Enterprise? "Star Trek: The Next Generation" and the Occupation of Femininity". Cinema Journal. 35 (2): 61–84. doi:10.2307/1225756. JSTOR 1225756.

- ^ "The Transporter Malfunction". The Big Bang Theory. Season 5. Episode 20. 2012-03-29. CBS. Retrieved 2018-01-19.

- ^ "20 Questions with... Kawa Ada". Toronto Stage.com. Retrieved June 9, 2018.

- ^ "Freema Agyeman Interview". October 17, 2007. Archived from the original on 2007-10-17.

- ^ "Jason Alexander Reveals His Trek Love". September 19, 2011.

- ^ "Bill Bailey interview". The List. 9 September 2007.

- ^ Duck, Siobhan (2007-06-13). "Who's a bad speller, that's who!". Herald Sun.

- ^ Cowen, Trace William. "Nicolas Cage 'Not Really Down' to Join 'Star Wars' Universe: 'I'm a Trekkie, Man'". Complex. Retrieved 6 October 2023.

- ^ Wright, Blake (October 1, 2009). "Exclusive: Stargate Universe's Robert Carlyle & Ming-Na". ComingSoon.net. Archived from the original on October 2, 2012. Retrieved October 6, 2009.

- ^ "George Takei interview". YouTube. 9 September 2016. Archived from the original on 2021-11-18.

- ^ a b Neumaier, Joe (2009-05-04). "Barack Obama, Angelina Jolie, Tom Hanks and more famous Trekkies". Daily News. New York.

- ^ a b c Kirsten Acuna (2013-05-17). "7 Celebrities Who Love 'Star Trek' More Than You". Business Insider. Retrieved 2018-01-19.

- ^ "Jim Davidson interview: 'I really want Stephen Fry to like me'". The Telegraph. 20 February 2014. Retrieved 6 October 2023.

- ^ a b "Treknobabble #35: Top 10 Hottest Celebrity Trekkies". Film Junk. 2008-10-09. Retrieved 2011-12-23.

- ^ Special Features. Star Trek: The Next Generation Season 2 DVD Boxset.

- ^ Pascale, Anthony. "Grunberg: 'Amazing Actors' Want To Be In Star Trek XI", TrekMovie.com, August 23, 2006

- ^ StarTrek.com. Catching up With Voyager Guest Star Virginia Madsen

- ^ "James Marsters reveals his fumbled Star Trek audition". Digital Spy. 3 July 2017.

- ^ Nimoy, Leonard (26 October 1995). I Am Spock. Hyperion. pp. 257–258. ISBN 978-0-7868-6182-8.

- ^ "Freddie Prinze Jr. Gives Blunt Reason Why He Won't Reprise Rebels' Kanan in Other Star Wars Projects, and William Shatner Would Probably Approve". 18 May 2023.

- ^ "Why You Should't "Sass" iCarly's Creator, Dan Schneider - YouTube". M.youtube.com. 2011-09-18. Retrieved 2022-05-19.

- ^ The New York Times [dead link]

- ^ The New York Times [dead link]

- ^ Anthony Pascale (2008-08-16). "Stiller Puts Some Star Trek In Tropic Thunder". TrekMovie. Retrieved 2008-08-17.

- ^ Ben Stiller (Actor, Director, Producer, Writer) (2001-09-28). Zoolander (DVD). Paramount Pictures. Retrieved 2009-03-17.

- ^ Ben Stiller (1996-06-14). "Cable Guy, The - Star Trek Knights". YouTube. Archived from the original on 2021-11-18. Retrieved 2010-02-19.

- ^ Nickinson, Phil (1970-01-01). "Television | Movies | Reviews | Recaps | What's On | www.whattowatch.com". Whatsontv.co.uk. Retrieved 2022-05-19.

- ^ Eric Goldman (2008-01-09). "Karl Urban: From Comanche Moon to Star Trek". IGN. Retrieved 2008-01-23.

- ^ Star Trek DVD commentary

- ^ "Star Trek: The Next Generation - Angel One", review on TVSquad by Wil Wheaton, 28 March 2008

- ^ Star Trek: Communicator issue 115, p. 65

- ^ Star Trek Monthly issue 49, p. 51

- ^ "Clint Howard Talks Discovery, STLV". StarTrek.com. 2023-07-25. Retrieved 2024-03-31.

- ^ "Interview – Planet Verge 2002". dragonninja.com. July 13, 2002. Archived from the original on February 17, 2012.

- ^ "The 5-minute Interview: Mike Oldfield, Musician". The Independent. London. 2008-04-07. Retrieved 2008-07-13.

- ^ "Roy Orbison - RIP Leonard Nimoy We are saddened to hear..." Facebook. Retrieved 2018-01-19.

- ^ "Elvis Presley named his horse Star Trek". montrosepress.com. Archived from the original on 2017-08-14. Retrieved 2017-08-16.

- ^ "Rihanna Cops to Being Lifelong 'Star Trek' Fan: Watch". Billboard. 2016-06-30. Retrieved 2018-01-19.

- ^ Billboard Staff (29 October 2015). "Carrie Underwood Freaks Out After Her Celebrity Crush Tweets About Her". Billboard. Retrieved 6 October 2023.

- ^ "Raves: D'arcy of the Smashing Pumpkins". Rolling Stone Magazine. 1996-03-07. Retrieved 2007-09-02.

- ^ "Zakk Wylde: 'Three Minutes On American Idol And I'm Somebody Now' | Interviews @". Ultimate-guitar.com. 2011-06-24. Archived from the original on 2011-12-03. Retrieved 2011-12-23.

- ^ "Entertainment | The King of Star Trek". BBC News. 1999-02-11. Retrieved 2018-01-19.

- ^ "Pete Buttigieg fills in for Kimmel, shows off 'Star Trek' knowledge with Patrick Stewart". Newsweek. 13 March 2020.

- ^ "Gesprek over de nieuwe Startrek-film" [Conversation about the new Startrek film]. nos.nl (in Dutch). 4 May 2009. Archived from the original on 2013-10-29.

- ^ Gail Collins (2000-08-18). "Public Interests; Al Gore as Fall Programming". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-11-06.

- ^ Pallasch, Abdon (2004-10-10). "Despite His National Reputation, Keyes Struggles to Find His Niche". Chicago Sun-Times. p. 28.

- ^ "Nichelle Nichols". Pioneers of Television.

- ^ Dan Stephenson. "The Shotgun: Your awesome Jack Layton image of the day". blogs.com.

- ^ Tieleman, Bill (2017-07-04). "Horgan Faces Galaxy of Star Trek-Like Perils". The Tyee. Retrieved 2020-12-01.

- ^ Israel, Steve. "As trial begins, Cheney's ex-aide is still a puzzle". International Herald Tribune. Retrieved 2018-01-19.

- ^ John McCormick (2008-03-07). "Obama a little confused about today's state". The Swamp. Tribune Company. Archived from the original on 2008-10-21. Retrieved 2008-11-06.

- ^ Matt Blum (2008-11-06). "5 Signs President-Elect Obama Is a Geek". Wired. Retrieved 2008-11-06.

- ^ Patrick Gavin (2009-05-09). "Trekkie in chief wants screening". Politico. Retrieved 2009-05-09.

- ^ "Better Know a District - New York's 25th - Dan Maffei - The Colbert Report - 2009-07-04 - Video Clip | Comedy Central". Colbertnation.com. Retrieved 2011-12-23.

- ^ Nemecek, Larry (1993). The Star Trek the Next Generation Companion. Pocket Books. ISBN 0-671-79460-4.

- ^ a b "Carlos Alvarado Quesada". Official Twitter account. Retrieved 13 July 2021.

- ^ "Remembering Reagan: The Klingon Connection". Official site. 2004-06-08. Archived from the original on 2004-06-14. Retrieved 2008-11-06.

- ^ "Alex Salmond reveals Star Trek obsession". STV News.

- ^ "'Matt makes me a better man' - Leo Varadkar's most revealing interview". Archived from the original on 2017-08-15. Retrieved 2017-08-15.

- ^ "David Wu (D-Oregon) - "Klingons in the White House" 10 January 2007

- ^ ""It's Not Science Fiction Anymore. We Will Have The First Woman President." - Rep. Ocasio-Cortez". Retrieved December 1, 2024

- ^ Dillard, J.M. (1994). Star Trek: "Where No Man Has Gone Before" – A History in Pictures. Pocket Books. pp. 22, 50. ISBN 0-671-51149-1.

- ^ Jasmine Gardner (2009-05-05). "Trekkie mania". London Evening Standard. Archived from the original on 2013-12-13. Retrieved 2017-01-20.

- ^ "How Startrek inspired an Innovation - your Cell Phone". Destination Innovation. 2012-08-08. Retrieved 2018-01-27.

- ^ Bradley, Laura (14 March 2018). "Stephen Hawking's Star Trek Cameo Remains Historic—and Delightful". Vanity Fair. Retrieved 6 April 2021.

- ^ Lasbury, Mark (2016). The realization of Star Trek technologies : the science, not fiction, behind brain implants, plasma shields, quantum computing, and more. Switzerland: Springer International. p. 283. ISBN 9783319409146. OCLC 957464794.

- ^ "Star Trek Bill Nye & a Bright Trek Future". Startrek.com. Retrieved 2018-01-19.

- ^ WIL WHEATON & Science of Star Trek - StarTalk with Neil deGrasse Tyson. YouTube. 6 December 2012. Archived from the original on 2021-11-18.

- ^ Tim Pritlove (2011-03-22). "RZ011 Astronautenausbildung" [RZ011 Astronaut Training]. Raumzeit-podcast.de (Podcast) (in German). Event occurs at 3:45. Retrieved 2018-01-19.

- ^ a b "NASA - Final Frontier Astronauts Land on Star Trek". NASA.gov. May 13, 2005.

- ^ "'Star Trek' Actors Beams Hellos to Astronaut in Space". Space.com. 7 February 2013.

- ^ "Star Trek Voyager, 2007 : Tracey Emin". Artimage. May 2014.

- ^ Cum Town - Star Trek. 2019-07-16. Archived from the original on 2021-11-18.